“Don’t think about making art, just get it done. Let everyone else decide if it’s good or bad, whether they love it or hate it. While they are deciding, make even more art.” —Andy Warhol

Monthly Archives: August 2014

“Where are the people?” resumed the little prince at last. “It’s a little lonely in the desert…”

“It is lonely when you’re among people, too,” said the snake.

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Philomena Lee and the Magdalen Laundries

Actor Judi Dench often plays unsmiling, all-knowing, uncompromising women who cannot be fooled, but in her Oscar-nominated role playing Philomena Lee in Stephen Frears’s film Philomena, she gives a unexpectedly soft, poignant and sympathetic performance that displays her versatility and range. The film is based on the true story of Philomena Lee, and Irishwoman who became pregnant as a teenager in 1951 and was sent to a remote Irish abbey during her pregnancy. There she was forced by nuns to work as a laundress alongside other unwed mothers, and was made to stay on working at the laundry without pay for four more years as penance for the sin of having had premarital sex, and to pay the abbey for the costs of caring for her during her pregnancy.

The practice of locking up young unwed mothers in what were known as “Magdalene asylums” or “Magdalene laundries” was common in Ireland and Britain in the 19th century, and it spread to other European countries and to the U.S. and Canada. The practice lasted well into the 20th century. The last Magdalene asylum in Ireland was in operation until 1996. At these workhouses girls were sometimes beaten, often locked inside against their will and sometimes forbidden to leave even after they became adults.

The Catholic Church enjoyed free labor from these women, and embarrassed parents of unwed pregnant teens were often so relieved to avoid the public shame of having their daughters’ sins paraded before society that many abandoned their children to the Magdalene sisters forever. Families often told neighbors and friends that their daughters had gone to live with family, or emigrated, or even died, all in an effort to save themselves from shame and social ostracism.

While these teen girls worked long hours in steamy laundries, their children were watched over by nuns in nurseries. At the abbey where Philomena lived, children were often adopted out to American married couples who sought children in return for generous donations to the abbey. Philomena’s much-loved son was adopted by an American couple and taken away without warning one day while she was working. She had no chance to say goodbye, she had no idea that her little boy had been flown to America, and she was not told that his named had been changed.

All her efforts to learn what became of her son were rebuffed by the abbey, which destroyed her records and denied knowledge of her son’s name and whereabouts. Ashamed by her plight but desperately sad to have lost her son, Philomena sought him secretly for a half century without luck. Finally, she enlisted the help of Martin Sixsmith, an out-of-work journalist and former government advisor to the Labour Party. Martin and Philomena traveled to America together and learned extraordinary things about Philomena’s son and the abbey’s deceptive practices. Their story of their adventure together was published by Sixsmith in 2009 in his book The Lost Child of Philomena Lee, described by the L.A. Times as “a serio-comic travelogue full of heart-rending discovery and the triumph of forgiveness over hate.”

Previews made it look like a manipulative tear-jerker about a naive old lady with a can-do attitude and a big heart, the sort of story that could turn sickly-sweet in under a minute. Happily, it stars Judi Dench and satirist Steve Coogan, two actors famous for their droll, whip-smart performances, and it benefits from the tart and clever writing of Coogan, who coauthored the screenplay. He is known for his cynical, sarcastic portrayals, and he shows his dark wit in films like The Trip and Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story. In England he’s well known for his most popular creation, a character named Alan Partridge described as “a socially awkward and politically incorrect regional media personality.”

I knew better than to expect mindless, treacly antics from Coogan or from director Stephen Frears, whose smart, often dark films include Dangerous Liaisons, My Beautiful Laundrette (which starred a young Daniel Day-Lewis), Prick Up Your Ears (with Gary Oldman) and The Grifters (a dark little masterpiece with John Cusack, Annette Bening and Anjelica Huston). Frears has no fear of difficult subjects or ugly moments. Weighing all these facts, I put aside my worries that this could be a manipulative little feel-good flick. Happily, I found it a movingly acted film about an unworldly, seemingly simple woman who turns out to be more complex and determined than people expect.

The battle between the jaded, antireligious cynicism of Martin and the every-day-is-a-gift devout positivity of Philomena is at the core of the film, but Dench’s portrayal shows the spirited openmindedness of our seemingly old-fashioned heroine. Her sense of hopefulness and appreciation for small kindnesses is nicely balanced by exasperation with Martin’s dour, dark, angry worldview. He is not won over by her endless sweet simplicity, but he is moved by her because he recognizes that she has insights into people and situations that he, with all his experience and inside information but lack of empathy, misses.

Martin recognizes that Philomena’s story is a door into a huge and devastating world of widespread, long-term institutional abuse of the most vulnerable among us: abandoned, pregnant teen girls and small children. He sees that she has a power to connect with people that he lacks because he is often closed to anything but the fulfillment of his own expectations and prejudices. The journey they take together becomes more tangled and difficult than they expect, and it becomes more personally engaging and meaningful than Martin could have guessed.

[Originally published on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

But Is It Art?

“Michael Jackson and Bubbles,” a life-sized porcelain sculpture by Jeff Koons, 1988.

I take art seriously, and often have very strong opinions about it. There are artists whose technical skill, taste or vision doesn’t match mine but whose work I can still respect and admire in some capacity. And there are a few whom I find so weak, irritating or vapid that I’ll admit to expressing some scorn for them in private. But while their work may not feel like it merits being described as art according to my internal art-o-meter, I am willing to be liberal in my acceptance of the use of the term “art.”

Multiple times, upon learning that I am an artist, I have had people tell me with big smiles and bright eyes that their favorite artist is Thomas Kinkade, and each time I bite my tongue and agree that his works are, um, quite cheerful. We can agree on that. Kinkade, the self-proclaimed “Painter of Light,” was hugely successful until shortly before his death in 2012. He was less an artist than a kitsch commercial illustrator with impressive marketing skills. He did not provide what I look for in an artistic experience, but he moved others, so when his admirers tell me how much they love his work, I do my best to show them respect. I may dislike the soft-focus, Kleenex-box-art style and subject matter of his work, but he touched people with his paintings, and their emotional reactions are real and important to them. Kinkade’s work prompts pleasing visceral reactions in people that bring them joy and comfort. So, much as his work turns my stomach, even it is art.

Essayist Joan Didion wrote, “A Kinkade painting was typically rendered in slightly surreal pastels. It typically featured a cottage or a house of such insistent coziness as to seem actually sinister, suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel. Every window was lit, to lurid effect, as if the interior of the structure might be on fire.” I must admit to laughing and nodding in agreement when I read those words.

The glowing houses, churches and street lamps in Thomas Kinkade’s paintings are extraordinarily popular because they evoke an instant and comforting emotional reaction in so many people. His imitations of light were meant to bring to mind thoughts and feelings of an idealized old-time American home life: clean, cozy, quaint, old fashioned, oozing charm and warmth. As a nation our taste often runs to the sweet, the peppy, the saccharine, and we admire and appreciate those who serve up our stereotypes in the most sanitized and friendly way. A man who sells reproductions of his paintings in the hundreds of thousands, many touched up with selected highlights by worker bees so that they look more like actual paintings than the cheap copies they are (so they can be sold for hundreds or thousands of dollars each instead of the ten dollars they might be worth), Kinkade understood his market and grew rich by never underestimating the public’s desire for clichéd and emotionally manipulative imagery. According to Wikipedia, he was estimated to have made $53 million from his art works from 1997 to May 2005 alone. Yet in the last few years of his life, the manufacturing arm of his empire went into bankruptcy and he experienced a backlash from formerly devoted franchise owners who said he had misled them and knowingly ruined their finances.

Thomas Kinkade’s subject matter, style, technique and execution give me the willies, but his work is art, albeit bad art. Some disagree with me, saying that merely evoking a cheerful reaction with one’s creations doesn’t make one an artist. Art may be meant to provoke thought and emotion, to make us ask questions, to challenge, confuse, reward or transform us. And decidedly bad art like Thomas Kinkade’s does indeed challenge, provoke and confuse me—usually in ways I find unpleasant. But not every work needs to accomplish every artistic goal. Art can exist merely to delight, to embellish, to decorate, to provoke laughter or to express whatever thought, feeling or impression the artist wishes to convey. Bad art is still art.

Art can elevate or soothe, excite or inspire. Many works which I revile are still, in my estimation, important art because they successfully innovate, surprise or make me think. Beauty speaks to the soul, and each of us finds beauty in different forms. We seek out things that please our eyes and our hearts. Art does transform, but it can do that through humor or subtlety, elegance, spareness or outrageous joie de vivre. Art can also be kitsch, and sometimes that’s great fun. Takashi Murakami‘s pop-art pieces are terribly popular, and though my favorites among them look a lot like the vinyl flower power stickers found all over beat-up VW beetles circa 1970, they’re fresh and freeing. They’re genuine art.

Art asks questions of its viewers. Sometimes it’s crude and confrontational, other times sly and amusing. It provokes anger, excitement, disgust, even tears. Other times it invites laughter or thoughtfulness, or merely prods us to stand still and feel. It is not a bad thing to feel comfort or simple pleasure. Schmaltzy art may not be high art, but art it remains. Obvious, twee and soulless prints feel like caricatures of landscapes to me, but they bring joy to millions. I look down on an artist’s decisions to use technical ability in the service of creating sub-par paintings with trite subjects with no aspirations to be anything more than derivative dreck. But whether I like it or not, it is still art.

Thomas Kinkade achieved something that many artists of integrity cannot: he managed to evoke strong feelings in many of the people who view and enjoy his work. Just because those of us with art history degrees may look down on untrained eyes as having inferior taste doesn’t mean that the feelings of those without our training aren’t real or legitimate. We may denigrate Disney’s homogenized, dumbed down, often sexist animated fairy tales for blandly pandering to the lowest common denominator, but the fact remains that the technical quality of their creations is usually superlative, and their understanding of the needs and desires of their market segment has been remarkably keen for nearly nine decades. They evoke genuine strong emotion with imagery so powerful that indelible icons come to mind when we think of Disney.

Watching Disney’s simplified versions of stories and illustrations supplant the more elegant, subtle or powerful imagery found in its stories’ source materials can be upsetting. Disney’s Winnie the Pooh animation is nowhere near as gorgeous as Ernest Shepard’s original illustrations for A. A. Milne‘s books are, for example. But Disney’s work is still art. It may not be high art, it may not always be good art, but it is valid art, as are Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ,” Robert Mapplethorpe’s S&M nudes, Picasso’s “Guernica” and Jeff Koons’s ridiculous, goofy and disturbing sculpture of Michael Jackson and his chimp Bubbles. Even Koons’s images of himself having sex with his real-life porn star ex-wife Cicciolina are works of art, if not art I’d want to own. Others’ artistic expressions don’t have to match our tastes to be valid. The art world is complex and ridiculous, but it also has endless room in it for an exciting panoply of expression—just like the rest of the world around us.

Capote

[Originally published on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

“My major regret in life is that my childhood was unnecessarily lonely.” –Truman Capote

The Truman Capote I grew up watching and reading was the Capote who appeared, usually drunk or drugged, odd but always interesting, on afternoon and evening talk shows, spinning stories about the fabulously famous and wealthy crowd with whom he ran. He was a professional personality by the time I was aware of him, but I also knew that he’d written much-admired stories that had been turned into very famous and popular films. I knew that my mother admired his work, and that he had written “A Christmas Memory,” one of the most beautiful, understated, tender stories I’ve ever read. The fact that it was based in his own experience made it all the more lovely to me. I felt sad for and protective of him at a young age, because I knew that the man who had written that story had been a tender and hyperaware child, like I had, and had seen the fear and pain in life as clearly as the joy and the secret beauties of it.

My mother taught “A Christmas Memory” to her high school English students for many years and she introduced it to me when I was about ten. I was completely taken with this story of a young boy abandoned by his parents and living with his disapproving southern aunts. This boy’s best friend was the childlike old-maid cousin with whom he also lived, a woman who flew handmade kites with him and took him to buy moonshine whiskey from Mr. Haha Jones so they could make their annual batch of fruitcakes, one of which they sent to President Franklin Roosevelt every year. Capote had taken the littlest details and moments in what others might see as an unexceptional situation and spun them into a rich and compelling story, simple and straightforward but with every word in place, every emotion sparely but elegantly woven into the words. I think it’s a short masterpiece; it is perhaps my favorite short story, and the one I’ve read more often than any other.

It was immediately clear to me that Capote got the tone, the subtleties, the story, and the total devotion of the characters for each other exactly right. That he was the model for the boy Dill in his friend Harper Lee’s story To Kill a Mockingbird, a novel that I find close to perfect, made him all the more special to me. I have read and reread “A Christmas Memory” to myself and others most of the Christmases of my life, and cry as regularly as clockwork when I come to the last bittersweet page. This was a man who clearly understood loss and loneliness, and who understood empathy and tender connection to another like few writers I’d come across. There was something beautiful and tender and true in him and in his art that I, and millions of other people, were drawn to, and wanted to believe in.

When Capote died in 1984 among swirling stories of long-term drug and alcohol abuse, he also left behind him a parade of disaffected friends who felt he’d used and abused them, that he’d betrayed their friendship and their secrets in order to steal their souls so that he might make not only his party anecdotes but his writing come to life. He had been such a wildly successful New York socialite, courting and collecting the loveliest, richest, and most prominent socialites as his “swans,” as he called them, for years. He hosted the New York social event of the decade, the famous and successful Black and White Ball, in 1966. Best-dressed list icons like Lee Radziwill and Babe Paley attended parties with him and had him to their summer homes, traveled with him and relished his delicious gossip. He wangled his way into the hearts of dozens of people who felt he understood them intimately and would respect and love them not only despite but because of their foibles. When he wanted to be charming, nobody could outcharm him. He made people of all types and of any social standing believe he loved them for the tender, misunderstood people they were inside their suits of shiny invincibility; they felt not only understood by him but safe with him. And then he spilled out their secrets for everyone to see.

For years he gathered their lives into his short stories and promised a splendid, insightful book to his publisher, talk show hosts, and the world, and we all waited with bated breath, knowing that when Capote had the time to build a work, like In Cold Blood, he would carefully piece it together just so and make the wait worthwhile. He had shown his mastery of the short story form very early in life, and, when sober, he was an insightful and entertaining fellow. He was also extraordinarily catty when he wanted to be, and, when one wasn’t on the receiving end of that acid tongue, he could be shockingly funny. But his charm was so extreme and his magical power of diverting attention from the things that everyone should have known that he was a sponge who missed no details, a writer first and foremost, insightful and ruthless when exposing the hidden motivation, the raw nerve.

So he gathered his swans’ secrets and then poured them out onto the page with such clarity, and so little effort at concealing the identities of his characters’ inspirations, that he immediately and permanently drove most of his friends and their associates away and turned their feelings for him from indulgent and loving exasperation to anger, fear, and resentment. To learn of how almost all the doors of society slammed on him one by one after he had been the toast of New York, the shining star of literary society, was to feel that, no matter how much he deserved what he got, it was still a terrible shame, that there must have been some mistake somewhere, some misunderstanding.

Knowing his downward trajectory during the last 15 years of his life makes “Capote,” the outstanding new film about his years researching and writing In Cold Blood, even more riveting. The film constructs, with not one extraneous scene or unnecessary bit of dialog, an understanding of his place in literary society, and his chameleon-like ease at blending into the lives of the people whom he wanted to capture and luring them into trusting him with their lives and stories. His ability to say exactly what a publisher, a murderer, his lover, his oldest friend wanted to hear in order to court their love or trust, and seem to mean each word he said, is juxtaposed rivetingly with his ability to cut them off at the knees, dismiss them, insult them, or ignore them when their needs don’t suit his. The performance by Philip Seymour Hoffman is astonishing, not only because his impersonation of Capote’s strained, high, tiny voice and his fussy mannerisms is so remarkably good, but because he moves effortlessly between charm and seemingly endless empathy to self-absorption of enormous proportion so smoothly and naturally. We both admire and revile him. In their roles, excellent actors Chris Cooper and Catherine Keener show indulgence and affection for him, as well as wariness and disgust with his deceit of others, of them, of himself. The script is often spare and the pacing, while perfect, is never rushed; what is not said by the characters is as important and full of meaning as the well-crafted dialog. We learn just enough about any character, any situation, to be able to piece together what its meaning will be to those involved. His actions and the reactions of others are carefully calibrated so that we are never in the dark as to what is going on or how his actions will reverberate, but we are trusted to be able to let the story build in our minds; the writer, director, and actors don’t spoonfeed us but deftly piece the feelings, words, and actions of the characters together so that the story builds and intermeshes exactly as it should. This is how a subtle story should be told.

Impressions on Impressionism

[Revised from an article originally published on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

When Americans think of art museums and so-called great art, Impressionism usually comes to mind. Impressionist artists and their work are among the most popular in traveling exhibitions and Impressionist paintings are frequently reproduced on coffee cups, calendars, posters, stationery and other gift shop items. The art section of any bookstore is likely to be well stocked with books on Impressionists; in fact, you’ll probably find more of them represented than you will artists of any other style or period. If you have children in public schools, any art education they’re likely to receive probably includes repeated lessons about and images by Monet, Van Gogh and Renoir, with some nods to Picasso, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci (who should always be referred to as “Leonardo” and not as “da Vinci,” by the way, despite what Dan Brown tells you—”da Vinci” isn’t a last name, but means “from the city of Vinci”).

Is this because Impressionists are better or more important artists than those who came before or after them? Probably not. Were they revolutionary? Yes, some of them were, some of the time. They emphasized a fresh way of seeing and of expressing what they saw, although artists had used loose brush strokes and tried to capture evanescent moments, the shimmer of gold, a quick impression of a lace collar or a glinting eye hundreds of years beforehand with fully as much wit and originality, to my mind. The influence of 17th century artists like Vermeer, Frans Hals, Rembrandt and Velazquez on the Impressionists is well-known. In fact, I find those original, inspiring 17th century works more beautiful, more exciting and more inspiring on the whole. The huge popular appeal of the Impressionists is largely because they’re more accessible; the pale colors are pretty, the shapes are indistinct and inoffensive, the subject matter is usually G-rated, universally acceptable and pleasing. Dark portraits of unattractive people, who were the subjects of some of the greatest works of the old masters, don’t have the same popular appeal as fields of poppies or women with umbrellas standing in sunny Provençal lavender fields. They look nice on cards to Grandma or on the dentist’s waiting room walls or on your office calendar. Pastels are pretty. Waterlilies are nice. We all like flowers.

Of course Renoir and Monet and their pastel-fancying contemporaries did see the world with fresh eyes and provided us with a new way of seeing and of expressing what we see. They are great artists, many of their works do challenge and please, and their works are worth knowing. But there’s so much more beauty in the world to challenge the eye and delight the heart, I wish people would look beyond the easy and obvious more often and think outside the Impressionistic box.

Some Impressionists move me greatly and delight my eye, of course. George Seurat’s pointillist masterpiece, “Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte” (“A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte”), inspired Stephen Sondheim‘s Broadway musical Sunday in the Park with George for a reason: it is bold and arresting, beautiful and unusual, and the placement of thousands of dots of paint next to other complimentary or contrasting colors in order to create a freshness, depth and a magical reaction in the eye is delightful and original.

Edouard Manet‘s portraits of demimondaines in paintings like “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe” (“The luncheon on the grass“) or “Olympia” are worldly and confrontational, darker and starker than the sweet mother-and-daughter paintings of Mary Cassatt or the rotund, soft-focus, spun-sugar nudes of Renoir, who sometimes look to me as if they were dipped in frosting and rolled in candy sprinkles. Manet handles the paint roughly and uses flatter patches of light and dark to evoke dramatic lighting and moods, and his characters face viewers unapologetically and draw us into their world with some force.

Van Gogh is justly famous for his sunflowers and irises and his starry night, and I do love them, but his more disturbing portraits of working people and of himself really prove him to be a master. His work reproduces badly because his impasto technique of applying paint so thickly to the canvas as to make it almost a bas relief is so vivid and three-dimensional, it simply can’t be adequately represented in a two-dimensional approximation. Also, we’ve become so jaded by the endless reproductions of his work, it’s hard to see them as fresh and original and world-changing the way they were when he painted them.

Among Impressionists one of my favorites is Gustave Caillebotte (roughly pronounced KY-uh-BOT). His compositions are bold but pleasing, and his mastery of perspective and prodigious technical skills are extraordinary. His angles are dramatic and add such movement and excitement to a painting, and the people within aren’t frantic even though they are active, on the go, moving toward or away from us at a steady clip and with a sense of purpose. “Jour de pluie” (“Rainy Day”) has people walking directly towards us and being cut off at the knees, they’ve come so close.

The way they’re cropped makes them seem that much nearer to us, and we see just the elbow of someone retreating, so he’s right on the edge of the picture plane, pulling us with him into the thick of the action. Then there are the smaller figures cutting across the middle and the one carriage wheel moving off to the left, so while our eyes are drawn to the couple approaching us, there’s just enough cross-traffic to keep our eyes moving through the layers of activity toward the back.

Finally, there’s that marvelous flatiron-shaped building on the left jutting toward us, and the perfectly receding wet cobblestones on the left and the modern sidewalk on the right bisected by yet another diagonal. All those diagonals and perfectly executed examples of perspective are at just the right angles to imply movement without cluttering the composition so much that we’d be left exhausted and distracted by too many competing areas of activity. There are enough places for the eye to rest before moving on to keep us from getting tired out by too much clutter, and those resting points give us enough time to satisfy our curiosity before we move on.

It’s pretty nearly perfect compositionally. Consider the languid, calm faces of the couple approaching us; they’re engaged and active but not frantic, and that keeps the attitude of the piece right, too; too much animation in their faces would feel like overkill in such a busy painting.

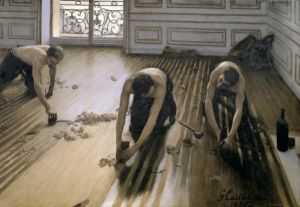

Another favorite painting of mine is Caillebotte’s “Les Raboteurs de Parquet” (“The Floor Scrapers”). The angles of the diagonal lines vary from left to right to accommodate the shift in our perspective because we’re standing in front of and above the planers on the right. Again, the perspective feels perfect and makes us feel we’re right in the room, part of the action, so close we can hear the wood curls being shaved up from the floor.

I love the shininess of the unplaned wood planks versus the dull pallor of the planed areas, and the fact that the planers are shirtless, their skin buttery and similar in tone to the newly planed wood. The only curves in the room are the curves of their heads and arms and arching backs, the curve of the liquor bottle and glass on the right, which promise relief from their tiring work, and the swirling arabesques of the wrought iron on the balcony shown through the glass door. The men, the bottle and the iron work look so much more sensuous and sinuous than they would otherwise because of the severe contrasting lines of the floor and the molding on the back wall.

This picture makes tiring manual labor and tedious craftsmanship look sexy. The fact that the men are shirtless also makes us think it must be a hot day, and that lets us imagine the smell of the wood shavings and sweat. The exciting combination of perfect composition and the implication of controlled but constant motion and intensity of focus of each man elevates a painting of three hot, tired workmen toiling on their knees to strip a floor, the most seemingly mundane of acts, into something extraordinary.

Again, each setting and each character within the setting is perfectly composed. Not only is the relationship between elements harmonious and pleasing, but the faces of all the people in each setting are calm, unaware of the gaze of outsiders (i.e., we, the viewers) who have burst into their presence. We’re just a short distance from them yet they remain distant from us emotionally, which lets us feel safer and less confronted by their proximity, so we can peer at them more directly without feeling challenged by them, like voyeurs. That a painter can create such realism and intimacy with imaginary characters by applying some oily pigments to a stretched piece of fabric is astonishing. To me, that is great art.

How Schoolhouse Rock Led Me to Jazz Great Blossom Dearie

[Originally published as “My Roundabout Introduction to Blossom Dearie” on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

When I was a child, ABC’s Saturday morning cartoon line-up was punctuated with wonderful short musical cartoons sponsored by Nabisco: the famous “Schoolhouse Rock” cartoons. The educational songs created for these cartoons were so clever, catchy, and memorable that they were all rereleased on video in the 1990s for the children of the children who enjoyed them over 30 years ago. I grew up on the “Multiplication Rock” and “Grammar Rock” videos; my daughter loved them 30 years later.

Much of the appeal of these videos was that each was just the length of a pop song, and the music and lyrics were written by proven and talented professional musicians, not by earnest professional pedagogues. They were quick and full of information, and had busy, funny animation. And they were the only regular music videos for kids on TV then; there were weak shows with live-action singers or talentless oafs in bad costumes doing pathetic songs, like on “New Zoo Revue,” and there were catchy theme songs on the somehow compelling yet also vaguely disturbing Sid and Marty Krofft kid shows like “H.R. Pufnstuf” (which starred Jack Wild, who played The Artful Dodger in the musical film “Oliver!”), “The Bugaloos” (whose villain was played by comedian Martha Raye, probably most famous to people my age as a denture adhesive pitchwoman) and “Liddsville,” that bizarre show about the land of talking hats starring Charles Nelson Reilly and Butch Patrick (a.k.a. Eddie Munster). But MTV didn’t exist yet and catchy musical TV ads for dolls or games (from “Life” to “Mystery Date“) were no match for three-minute musical cartoon masterpieces like “Three is a Magic Number” or “Conjunction Junction” or “I’m Just a Bill.” These songs were so good that a number of popular rock bands covered them on the album “Schoolhouse Rock Rocks.”

Of all the songs in the “Schoolhouse Rock” oeuvre, there was one that shone out as a particularly elegant little gem: “Figure Eight.” My mother loved it so much that she bought the “Schoolhouse Rock” album on vinyl many years ago just to listen to that song. This ode to the number eight was illustrated by a figure skater and the song was sung by a woman with an unbelievably darling name and voice: Blossom Dearie. The dearest part is that she was born with that name. And the best part is that sweet, small, clear voice has sung some of the lightest, crispest, most refreshing versions of a number of jazz standards I’ve ever heard. She also has a fresh, spare style of piano playing that underscores that little pussycat voice.

I remember seeing Blossom Dearie interviewed on TV in the 1970s; she had wit and sparkle, and I was rather amazed that her tiny little voice seemed not to be a put-on but the real deal. When I started listening to her recordings of jazz standards years later, I found there was less cutesiness than I expected, and more of a wistful, light yet wry quality to her singing. I love the way she delivers Dorothy Fields‘ lyrics in “I Won’t Dance” (“For heaven rest us, I’m not asbestos”) and the light but knowing quality of “They Say It’s Spring.” “Rhode Island is Famous for You” makes my daughter and me laugh, and it’s fun to compare her version of that song to Michael Feinstein’s. While I love Feinstein’s direct, swoony, passionate if sometimes campy treatment of lyrics, and think he does that song well, Blossom Dearie’s delivery has a quiet humor and a conspiratorial wink, whereas Feinstein’s is more of a showman’s romp, bigger and bolder and more obvious. Both have their place, but Dearie’s intimacy makes me feel like I’m in on a more sophisticated joke.

Can’t Sleep, Clowns Will Eat Me

I’ve never cared much for clowns. I don’t have coulrophobia (fear of clowns), though this fear is apparently surprisingly common. I just find pretty much everything they are and most of what they stand for annoying. I don’t hate them, but I avoid them when I can, and I’ve been sorely tempted to buy myself a “Can’t sleep, clowns will eat me” T-shirt. Apparently many of my fellow Americans agree with me.

My beloved Uncle Steve is the exception to my anti-clown rule. He finally retired from his recurring role as Tidy the Clown in the annual Redwood City (California) Fourth of July Parade after 25 years of clowning around in public, and I must say I did enjoy him. But he was a gentle clown who pushed a bottomless garbage can down the street, popping junk into it and leaving a trail of trash behind him as the debris went right through the bottom of the can. When he’s a clown, the joke’s on him, and the audience gets to giggle at his cluelessness.

Steve’s alter ego, Tidy, recruited elementary school kids to be his clown sidekicks every year, and the result was charming and sweet. Tidy stuck flowers into piles of pucky left by the horses of the mounted police that went before him, and only approached people if they seemed open to it; he’d never force himself on a child. He’s more the sweet, Chaplinesque Little Tramp sort of clown, not the barrelling, bamboozling, freakazoid clown one finds on, say, ice cream cone packaging. (That is one horrifying dude.) I can make exceptions for someone like Tidy, but in general, keep Bozo and his ilk far away from me.

The sort of clown my uncle represents is endearing and enjoyable, a sort of old-style, mid-20th-century, fun-loving clown. But nowadays such cuddly clowns are rather rare. The cheerful, perky clown toys of the past have given way to more garish and ghoulish representations in the general media.

The general idea of the American clown, a white-faced social misfit clad in oversized and odd clothing, ignoring people’s personal space, attacking them with seltzer bottles or squirting flowers, and using them as the butt of public jokes as a way of seeking attention, pretty much sums up the worst of American behavior in one self-parodying, campy, over-the-top package. It’s nearly everything I hate about our embarrassingly accurate national stereotype: garish, self-absorbed, pushy, willing to trod on other’s toes, thinking our needs are greater than everyone else’s, ever ready to laugh at others’ humiliation but in a touchy, bad-humored funk when the table is turned and the joke’s on us.

To be fair, clowns of other cultures (e.g., buffoons like Pantalone and Arlecchino in the commedia dell’arte tradition, or Britain’s Punch and Judy puppet versions of clowns) are also caricatures with distinct, overscaled features, costumes, and gestures, all of which predate the founding of the United States by many years. I’m being unjust in blaming American culture for the American clown tradition, I know. They come from a long and, to my sensitivities, annoying tradition of making the audience the straight man, barrelling over others for laughs, and making light of humiliation and slapstick violence. It’s the sort of thing that Roberto Benigni did in his Holocaust-lite Oscar-winning crowd-pleaser, “Life is Beautiful,” a few years ago—much to my disgust and dismay. For a description of the film that agrees with my take on it, see David Denby’s review, “In the eye of the beholder,” published in The New Yorker, March 15, 1999. I found nearly everything Benigni did in that film either offensive, maudlin, self-aggrandizing, disrespectful, or embarrassing—or all of those things rolled into one.

I’m not actually a humorless prig; I can cackle and guffaw with the best of them, and I laugh so hard I snort more often than I care to admit. I can enjoy dark humor, tacky humor, vulgar humor, but I can rarely appreciate or enjoy slapstick physical comedy or farce, unless they’re so bizarrely irrational (e.g., my beloved Monty Python) that it’s impossible to empathize with the person playing the butt of the joke. Otherwise, I usually become uncomfortable when the laughs come at the expense of someone else’s pride, safety, or happiness. Even when the straight man is set up to seem an unpleasant sort who deserves his comeuppance, I generally don’t like seeing others derive happiness from the suffering of others. But then, I don’t appreciate most light romantic comedies, either. I can watch “Six Feet Under” or “The Sopranos” all day long (gimme that angst!), but ask me to watch ditsy women trip over themselves to get the attention of pretty boys with great abs for an hour and really, I’d rather floss my teeth or weed my garden, thank you very much.

Of course, I’m not alone. A quick search of eBay will find you scores of scary clown puppets, figurines, and posters that the sellers recognize as distinctly creepy. A walk through the aisles of your local Blockbuster shows DVD covers emblazoned with killer clowns in the horror section. “The Simpsons” even featured an episode in which Bart is so frightened by the clown-inspired bed Homer makes him that he stays up all night chanting, “Can’t sleep, clown’ll eat me.” This is apparently the genesis of the refrain now printed on T-shirts worn by proud coulrophobes across the nation. (Leave it to Matt Groening to explore odd undercurrents of our nation in such a fun and funky way.)

I don’t know whether it’s worth it to resurrect cheerful, inoffensive clowns, since even they had elements that have scared children for centuries; outsized features, crazy make-up, and disturbingly child-like behavior coming from an oversized adult are just odd. I prefer my comedians to take the forms of everyday people, I guess. I like my fantasy worlds to feel as close to a world I can believe in as possible, so I can get lost in them more easily. Some like fantasy characters and scenarios to be as outlandish as possible in order to feel truly immersed in another world and way of thinking, but I’d rather have some emotional connection to fictional characters so that I can care about them and identify with them, and for me, that usually involves making them feel as much like realistic human beings as possible. I also prefer it if they don’t step out of their boundaries and squirt me in the face with a shot of seltzer water. I’m funny that way.

[Originally published in Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

“It is difficult to produce a television documentary that is both incisive and probing when every twelve minutes one is interrupted by twelve dancing rabbits singing about toilet paper.” —Rod Serling

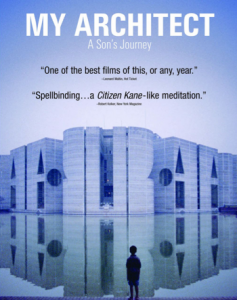

My Architect: A Beautiful Documentary

[Originally published on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974) was one of the 20th century’s most influential and well-regarded architects. He designed such important structures as the Exeter Library at Philips Exeter Academy, and the Capital Complex in Dhaka (Dacca), Bangladesh, and his work was revered by high-flying architects such as I. M. Pei, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry. But his habits of overwork and overextension, bidding for too many projects and becoming obsessive about his all-consuming passion for architecture, led him to die of a heart attack, bankrupt and alone, in a Penn Station bathroom as he was on his way home to Philadelphia from New York. When he died, he left not only a wife and their daughter, but also a mistress and his second daughter, as well as a second mistress and his third child, his 11-year-old son, Nathaniel, who made a beautiful documentary about his father, “My Architect: A Son’s Journey.”

Nathaniel Kahn’s documentary visits and discusses the works of his father, some of which Nathaniel had never seen before, and shows the emotional and artistic impact that Louis Kahn and his work made on others, both architects and clients. But more than being a simple homage to his father and his works, the film shows Nathaniel’s search to understand his secretive, mysterious father’s compartmentalized life and to strengthen his connection to the father he lost so early. Louis Kahn’s charisma and charm, his love for his children and the feelings of great love and loyalty he engendered in the women in his life are all made clear, as are his self-absorption, his need to make every commitment in life secondary to his commitment to his work, his flashes of arrogance, and his lack of empathy for others. The question which underpins the whole film is whether the gifts of an artistic genius whose work engenders tears of appreciation from his clients and fellow architects can justify his remote, selfish, and disconnected life.

To his credit, Nathaniel Kahn doesn’t try to answer any of these questions once and for all; he interviews his two half sisters and talks with his mother, who still nurses the belief that Louis Kahn was about to leave his wife and come to live with Nathaniel and his mother before he died. He asks difficult questions and presses his mother to be honest about his father’s failings and selfishness. The responses are at times surprising and always sad and touching.

Although he admires his father’s work, Nathaniel Kahn doesn’t like every one of his father’s buildings. As he makes his pilgrimage to each one, he asks the people who live with and use the buildings how they feel about them, and admits when he finds one cold or impractical. When he visits the Exeter Library or the Institute of Public Administration at Ahmedabad, India, or when he goes to Bangladesh and sees how the Capitol and Parliament Buildings in Dhaka are enjoyed and made into the center of life for the local people, he is clearly moved. Sometimes the technical mastery of his father’s work, its appropriateness in shape, form, and function and its original and spare use of light and materials awe him, and we see him surprised and touched by the effect that his father’s work had on others.

It’s difficult to express what makes this film so watchable, moving, and fascinating. I suppose it boils down to three things I find endlessly illuminating: artistic masterworks, biographies of unusual and influential people, and bad family dynamics. This documentary is worth watching on any of those counts; as a work of art encompassing all three, it’s extraordinary.

I found a lovely site with beautiful photographs of Louis Kahn’s work; do check out “The Works of Louis I. Kahn: A Visual Archive by Naquib Hossain.” Hossain describes Kahn’s work elegantly as “A purposeful knot of complements and contradictions in a rich fabric of brick, mortar, and concrete, woven to being by natural light.” “My Architect” is a purposeful knot of complements and contradictions, too, and a lovely work of art in its own right.