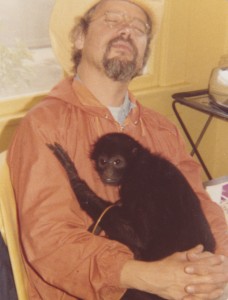

My father and his monkey friend, 1979.

My witty, bright and difficult father would have been 76 today. He was creative and talented, and he had a way with words. He also had serious problems with alcohol and anger, and he treated his child, his wives and his siblings with sarcasm at best, with arrogance and disdain as a matter of course, and with violence at worst. He was very good at one thing, though: he was extremely generous to down-on-their-luck people to whom he owed nothing.

My parents met when they were students at UC Berkeley. When my father was a psychology teaching assistant at Cal, he worked with autistic kids before most people had ever heard of autism, but shortly after he married my mother he became disaffected with his professors and left his promising career in psychology behind. My parents fell in love and married quickly, before my mother realized what a volatile and combative man he could be. My father’s alcoholism became apparent as soon as they were married, but by the time my mother realized what sort of man she had wed, she was pregnant with me. His violence toward her began even before I was born. By the time I was four months old, he had already hurled his glasses across the room in a fit of rage when I, who had been born two months prematurely and was still tiny and fragile, would not stop crying. My mother had left me alone with with him for the first and only time during my infancy so she could go grocery shopping. She came home to find him fuming and holding his broken glasses. Mercifully, they separated shortly afterwards. His bad health and alcoholism were already losing him jobs by then, and he stopped paying child support forever shortly after my first birthday. But my mother realized that even without his help, raising me on her own was the best decision she could have made.

Yet my father was not always bullying, threatening, drinking or shouting. When my mom was pregnant with me, he made me a beautiful cradle out of an old barrel. He was good at making something useful and beautiful out of nothing. Years later, from discarded bicycle parts he created usable bikes for himself and his poverty-stricken friends so they could have free transportation to school and work. He was disabled by serious health problems and unable to work for more than short periods of time for most of his life, and the benefits he received for being a veteran with serious health problems (he’d lied about his age to enter the Navy at age 16) didn’t go very far. But out of a few hundred dollars a month in disability payments, he paid the rent for his room in a dingy, sad hotel and spent the rest on cheap canned foods, books and used clothes so he could keep himself and his neighbors warm, fed and educated. He fixed their broken appliances, helped them write their résumés, computed their taxes, babysat, and, occasionally, he hid their drugs for them when they were afraid of getting raided by the cops. He had almost no respect for authority, and this caused him enormous problems throughout his life but made him popular with his troubled friends.

My mom had wisely left him as soon as she realized that his violent streak made him a danger to me, but she welcomed him to our house to pay me visits once I was a precocious toddler who could talk and follow orders. She figured I’d be physically safe around him at that point, and I was. But sometimes he’d show up two hours late, other times not at all. His brother, my beloved Uncle Steve, drove across the Bay Area several times a year to retrieve and sober up my dad, who was sometimes still drunk at 10 a.m. Steve would make sure my dad took his desperately-needed medications, feed him and calm him. Then Steve chauffered my father to my home and chaperoned our meetings. Steve made jokes to lighten my dad’s spirits and distract me from my father’s dark moods and sarcasm, and he bought us deli sandwiches and took us to parks to walk and talk and look at nature. It was Steve who drove my dad back home and soothed him after we said goodbye. If it weren’t for my dear uncle, I would have almost no memories of my father, and my father would have had little idea of who his sensitive, expressive, hungry-for-approval daughter was.

Dad was angry, bitter, depressed and occasionally delusional, and for years at a time he’d refuse to see or talk to me when he was ashamed of his behavior. He would become angry at me for expressing dismay when he called me in one of his drunken stupors to promise things he would never deliver, to tease and sometimes mock me, and to tell me ugly stories about his raw adventures among the downtrodden. I had to trick him into seeing me and my daughter when she was a baby, and though he fell in love with her immediately, his mental problems caused him to withdraw from us again immediately afterwards. He died a few months later having only met her once. No matter how much I wanted to make him a part of my life, he usually refused. I tried to be as perfect, entertaining and gregarious as possible every time he showed up. I could not call him because he was often without a working phone, but I created elaborate cards and drawings for him, and spent hours decorating the envelopes I sent to him with intricate drawings to try to entice him to communicate with me. It rarely worked, and over time I finally realized that this rejection wasn’t about my value as a person but was based in his own fears, pain and self-loathing.

After he died, I spent a lot of time at the sad hotel in which his life had ended. He was a hoarder, so it took me weeks to clear out his single room of all the tall piles of possessions: the small appliances, the books that covered his bed two feet deep so that he was forced to sleep sitting upright; the canned goods and free weights and dressers full of warm clothes; the manuscripts and letters to the editor and the letters to himself that disclosed the depth of his mental illness to me after his death. But while clearing things out, I met several men who had lived in his building and valued his friendship immensely. They told me of the kindnesses he offered them, and after I’d donated most of his clothes to the thrift shop across the road, I realized I should offer everything else in his room to the men who lived alongside him. They were thrilled to have his typewriters, his radios, his food and books and Playboy magazines.

His friends spoke of him as being both cantankerous and immensely generous. My father’s siblings and my mother, who had known him in better times, were happy to learn that despite burning every familial bridge thoroughly and repeatedly, he had managed to salvage some essential good within himself and show it to a few souls even less fit for the world than he. These stories and his writings, which disclosed to us just how far his thinking had strayed from reality, helped us to recognize how much his retreat from us had been a response to his self-hatred and his fear of harming us again. Though he’d blamed us all for his distance and unkindness at one time or another, we knew that he was picking fights in part to have an excuse to keep away from us to avoid doing further damage to those whom he loved.

No matter how many years I spend trying to understand what made him break so many promises and do so many cruel things, I will never entirely understand what caused him to disintegrate so seriously. But I do know that within him was a man who cared deeply about the earth and about animals, who honored labor and learning, who championed progressive values and believed that we all deserved dignity and respect, even if he himself didn’t always treat others as he should have. He loved me as deeply as he could love anyone in the world, and he was delighted and soothed by having met my baby girl. And as hard as my life has been at times, I am still grateful that he and my mother gave this life to me, in all of its painful, scary, magical, beautiful glory.

For all his many faults, my father helped to teach me to love nature, wordplay, movies and pickles and storytelling. He helped me to always hold a place in my heart for those who falter, who fail and who are too afraid to reach out for help. He helped me to see why some people self-medicate and don’t communicate with those whom they love most in the world, even when they want to. Through his failures I learned to be more careful about judging those who screw up, to have more respect for those who live on government assistance of one sort or another, and to have sympathy for those who come back from military service plagued with violent thoughts and dangerous tempers. Even when such people disappoint or scare or frustrate me, I can usually remember that underneath it all, they are just fragile people with fears, troubles and pains I can’t understand that cause them to do harm when they want to be helpful, and to break things when they want to build them.

Happy birthday, Dad. Thanks for giving me life.