Photo of a Tupperware party by Bill Owens from his book Suburbia

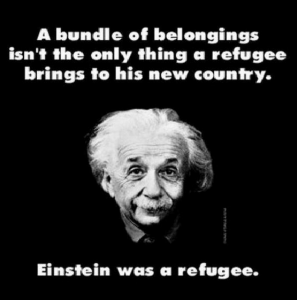

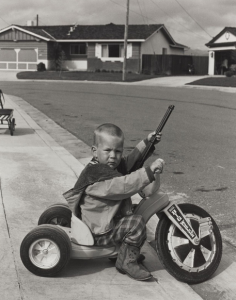

When I was a child growing up in the San Francisco suburb of Livermore, the publication of photographer Bill Owens‘s exploration of Bay Area suburban life, Suburbia, was a big deal in my home town. His book of photojournalism, published in 1973, garnered significant media attention; it was even written up in Time magazine. The book was of particular interest in Livermore because its stars were our town’s own citizens. The Tupperware ladies, toy-gun-toting little boys, Barbie-collecting girls and block party barbecuers whose black-and-white portraits filled the book lived in the Livermore-Amador Valley. Several of my mother’s friends and our own family doctor appeared in its pages.

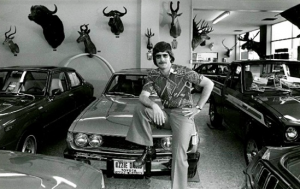

Even now, historians, postcard manufacturers and bloggers republish photos from the book. Art galleries, major museums and other institutions around the world include Owens’s photos in exhibitions. Gallerists and pop culture historians point to his work when they want to expose the supposedly tacky superficiality of American suburban life during that awkward period between the clean-cut, rule-following fifties and the shaggy, sexy, if-it-feels-good-do-it seventies.

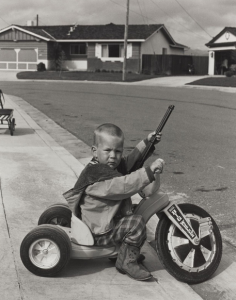

Photo of six-year-old Richie Ferguson by Bill Owens from Suburbia

Bill Owens took these now-iconic photos when he was a staff photographer at the Livermore Independent News starting in 1968. My mother’s boyfriend at the time was himself a reporter at the Independent who worked alongside Owens, so I met the photographer at a party shortly after the publication of his book. He had the no-nonsense confidence of a man who is used to sizing up a situation quickly, figuring out the most visually compelling elements, and getting in and out of an event in a hurry, before his subjects have a chance to become too self-conscious or studied in their poses. News photography has always required such skills, but in the days of film photography, there was a pressing need to be able to edit one’s work on the fly and be quick about it. Film was costly, and all photos needed to be developed and cropped by the photographer on short deadlines if they were to make it into the next day’s paper. Taking too many shots or too much time was a luxury that local papers and their staff photographers could ill afford.

In the seventies, there were few television channels or news radio stations, and of course there was no Internet with which individuals could share news directly, so the local newspaper was the primary source of in-depth information on all things regional. Newspapers had to report on crime, business, sports, laws, fashion, civic and social events, so photographers like Bill Owens had to get in and out of multiple places and events daily. But while Owens came from that journalistic tradition, in his photoessays he took the time to focus not only on what people did, but also on how they felt about their lives and suburban surroundings. He let his subjects express their pride, ambivalence and concerns about living in a growing, post-war, middle-class community. It was a time of prosperity and expanding social and sexual openness, but also a time of war, increasing crime and political unrest. Our town was largely insulated from the drama and violence that was shaking bigger cities at the time, but middle-class angst and drama were plentiful.

In his photographs and in the commentary his subjects provided, Owens caught suburbanites in private moments. They questioned whether they were capable parents, or took pride in living what they considered to be the good life. Some admitted that while they’d found the money to buy a house, they couldn’t afford to furnish it. People opened up to him, agonized over whether they were setting good examples for their kids, beamed as they showed off their prosperity, or sat half-naked on the edge of a bed daring the world to judge them for being comfortable with themselves.

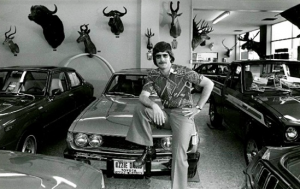

Photo of Livermore’s Ozzie Davis Toyota dealership by Bill Owens from his book Suburbia

The world was used to urban photographers like Diane Arbus or Gordon Parks taking awkwardly intimate photos of people looking embarrassingly real in big, gritty cities like New York. Time and Life magazines brought images of war and rioting into our homes each week in full-color photo spreads. In comparison to large-scale photojournalistic works about the Great Events of Our Time, a photoessay treating the inhabitants of a middle-class enclave near San Francisco as if they were significant enough to be worthy of their own project was a fresh and intriguing idea. It was exciting to be in the spotlight after always feeling like we had been on the edges of things.

Livermore is less than an hour from San Francisco, which was the hippie movement’s Ground Zero during the 1960s. Though only a half-hour from Berkeley, scene of some of the nation’s most bitter and frequent anti-war protests during the years when these photos were taken, Livermore had for many years been a bastion of traditional conservative values.

A wine-growing community dotted with ranches, Livermore was known as little more than a cow town until the early 1950s. My high school’s mascot was a cowboy, and the street behind the main school building is still called Cowboy Alley. But while the community had long been based on rancho culture, by the 1960s and 1970s Livermore’s biggest employer was what was known as the “Rad Lab,” rad being short for radiation: Livermore was and is the site of one of the nation’s largest national nuclear weapons laboratories. What is now known as the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory opened its doors in 1952, and by the time Bill Owens’s book was published two decades later, the laboratory directly employed about 10% of the city’s population.

For six decades, Livermore has had one of the largest concentrations of top nuclear physicists in the world, meaning that my town was home to a huge number of highly educated, fact-loving scientists, their well-educated spouses, and their smart and skeptical kids. Most of those who worked at the lab were strong believers in the theory that the specter of “mutually assured destruction” by the Soviet and U.S. superpowers in case of a nuclear war would keep either side from initiating war as long as both sides kept designing, building and stockpiling more and more threatening, long-range and expensive weaponry.

The Cold War-era belief that spending billions on the development and creation of weapons of mass destruction was necessary to keep us safe from communists (who were building their own gigantic nuclear arsenal on the other side of the world) sounds like a conservative stance to us today, but there were plenty of political moderates and even liberals working at the lab. Democrats like Presidents Kennedy and Johnson were staunch anticommunists who had instigated and escalated our involvement in wars meant to stop the spread of communism. Fear of communist expansion and take-over was by no means a solely Republican fear. Engineers and physicists who prized rational thinking above all were often open-minded and modern in their thinking in many fields and they came in many political flavors, not just conservative ones.

By the time that Bill Owens set about photographing our city’s denizens, formerly rural Livermore’s population included many erudite, cultured people of all political persuasions who were curious about the world in general. Many of the problem-solvers who had descended on Livermore from around the globe brought with them great worldliness and interest in culture and erudition. Though Livermore had once been thought of as a quiet farming community out in the boonies, by the 1960s it was surprisingly full of eclectic amateur theatrical events, excellent public schools with award-winning musical ensembles and a community symphony. An ambitious annual cultural arts festival takes over much of the downtown corridor during early October every year to this day.

However, because of the popularity of Bill Owens’s book, the place where I grew up became famous for people who represented everything superficial and embarrassing about suburban American culture. The real Livermore was a lively mixture of experts in fields from agriculture and livestock to nuclear weaponry to the arts. The book that both celebrated and embarrassed us was on the coffee table of every hip and educated family in town, and we felt both pride and chagrin over the images shown within its pages. There was delight over the fame the book brought us, and recognition of ourselves in the photographs and stories told in the book, but also a bit of shame over the parts of the book that made us look like overconsuming, self-absorbed buffoons.

Another understandable but misleading aspect of the book was the fact that the long agricultural history and natural beauty of the place got lost in the focus on the tract housing developments and accoutrements of post-war Northern Californian living, so the richness of the culture and the long history of people living close to the land in Livermore and the surrounding valley all but disappeared.

Big cities like New York can handle having people think a large proportion of their citizenry is odd or tacky, but Livermore has suffered unfairly over the years by having people choose the least flattering photos and stories from our signature photoessay to represent our whole populace. Although those of us who lived in the Bay Area in the early seventies grew used to hearing that our region was rife with proto-New Age philosophies, encounter groups, redwood hot tubs, free love experimentation and all varieties of omphaloskeptic behavior, for many people (like my self-righteous hippie father) Bay Area suburbs like Livermore came to represent not the cool, sexy, mind-expanding elements of the Age of Aquarius but the shallow, consumerist, un-self-aware aspects of modern living.

In the decades since I left Livermore, the city has nearly doubled in size thanks to its proximity to the tech boom in San Francisco and Silicon Valley. My home town has long been one of the more affordable corners of an outrageously overpriced region. It is still home to one of the nation’s top nuclear weapons laboratories, as well as to Sandia National Laboratories, which develops, engineers and tests the non-nuclear components of nuclear weapons. But its economy and culture are no longer quite so closely tied to the nuclear research culture as they were when I lived there. Yet echoes of that culture reverberate in modern literature and film: the writer of the popular science fiction novel The Martian, Andy Weir, grew up in Livermore. He went to my high school, worked at Livermore’s Sandia Labs, and he is himself the son of a particle physicist who worked at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. It’s likely he had a literature or composition class with my mother at some point; I like to fantasize that she may have encouraged his considerable writing talent in some small way. Though Weir wasn’t even born when the first of the photos in Suburbia was taken, the influence of Livermore’s science-friendly, intellectual, problem-solving culture helped to nurture his curiosity and imagination, just as it did my own.