In honor of Sammy Davis Jr.’s 100th birthday today, I’m sharing this piece I originally wrote about him back in 2006. Thanks again, Sammy.

A few months ago, I was doing a difficult job that lasted six weeks instead of the two I thought I’d signed on for. I was commuting about 10 hours a week (and I hate driving), and the job required intense focus on thousands of important details. I learned a lot, the people were kind and helpful, and the work they did was important, but I felt out of place, frustrated, and blue.

I tried reminding myself of all the things going right with the job: I was employed, working with good folks at an institution that improves people’s lives, making enough so that I didn’t have to work two jobs, and setting a good example for my daughter by showing that sometimes we do things we don’t enjoy in order to pay our dues, fulfill our obligations, be helpful, and earn a living.

Of course, while my brain understood all this, my heart felt cranky and sad. I was frustrated that the talents I feel are the most valuable and worthy ones I have to offer weren’t being used to the extent I’d like to use them. And then I had my Sammy Davis Jr. epiphany.

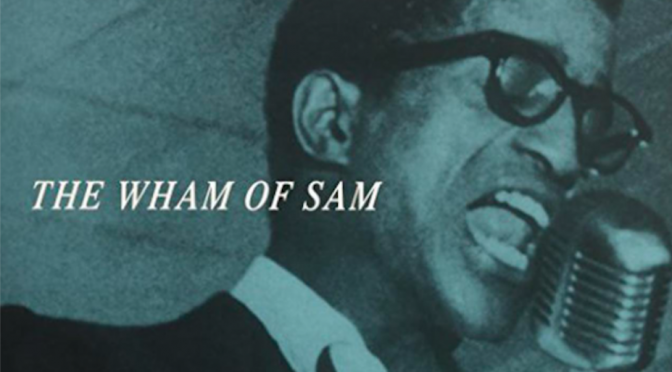

To try to make the hours in stop-and-go traffic feel less gruesome, I realized I needed to find fresh and uplifting tunes. I love NPR (which recently featured an interview with Sammy’s daughter, Tracey, who discussed her new memoir of her father), but sometimes focusing on the latest events in Fallujah while stuck on a bridge for 30 minutes just feels too nasty and I need music. I rummaged through my CDs and found one I’d bought a few months back but hadn’t listened to much yet. It was a CD of songs performed by a man I must now admit I used to think of as one of the poster children of Vegas kitsch: Sammy Davis Jr. But the best part is the name of the album: “The Wham of Sam.”

I must digress at this point. Are you already asking yourself, why would Laura buy Sammy CDs in the first place? Well, because I heard one of his songs in a store somewhere and was reminded what a fine voice and a great sense of expression, style, and warmth he had at his best moments. The many TV appearances he made during the 1960s and 1970s were so filled with Vegas schlock and corny stylization that he was almost a self-parody by the time I started listening to music in earnest. He was doing campy, obvious, cool cat riffs during his showy performances with Merv Griffin and Mike Douglas and on The Tonight Show, and I couldn’t be bothered. I knew I’d loved his portrayal of Sportin’ Life in the film Porgy and Bess when I’d seen it on TV as a tiny kid, but I don’t think it’s been on TV since about 1970 so my memory is now faint, and I loved his performance as the Cheshire Cat singing “What’s a Nice Kid Like You Doing in a Place Like This?” in a strange 1966 animated parody variation of Alice in Wonderland.

His turn as groovy evangelist Big Daddy in Sweet Charity is a classic sixties moment that featured Sammy’s charismatic rendition of the song “The Rhythm of Life,” but somehow I forgot about that. The big hits he had when I was a kid, like “The Candy Man,” felt too cutesy and pat to me, and I dismissed him, with his goofy hipster patois and giant diamond rings, his membership in the Rat Pack, and his public support of Nixon was too bizarre. (I still shudder when I remember the much-publicized photo of Sammy’s adoring, awkward, full-body hug of Nixon.)

But when I heard him singing over the speakers at some chain store I thought, damn, no wonder this man was so popular. Listen to the feeling he puts into that line! What clear, clean enunciation! What sophisticated, tasty phrasing! So I swallowed my pride and hung out at a CD store listening station for a half hour, listening to selections from a number of his albums. I bought two, one of ballads and one of swingier songs. What a good move that was. But then I got distracted and hardly listened to them.

Anyway, back to my commute-hour epiphany. I popped “The Wham of Sam” into my CD player, and right there, boom, I was hooked with the first song, the star of the album, “Lot of Livin’ to Do.” The horns grabbed me immediately, and the energy, which starts out high, somehow continues to build with every measure of the song. The band arrangement by Marty Paich is fabulous, swingy in the style of Sinatra’s terrific “Ring-A-Ding-Ding” album (one of my favorite albums of all time, by anyone—it was arranged by the legendary Nelson Riddle).

“Lot of Livin’ to Do” is big and brassy and has something new going on at every turn, but the band never outshines Sammy, whose phrasing is exact and elegant. His syncopation is so sure and it builds right up to the payoff moments. He knows when to pull back a little and when to let it rip. The intonation and enunciation are beautiful, but beyond his technical chops, he works the lyrics just right. He’s thinking about what he’s saying, he means what he’s singing, and I believe every word. He was sizzling and I was thrilled, sitting in a traffic jam on a bridge near Seattle at 8:30 a.m., bouncing up and down in my seat.

I must have listened to that song six times in a row on the way into work. The words crept into my brain and Boom! I had a revelation. The words aren’t Shakespeare; they’re standard upbeat lyrics, and the song was originally written for the musical Bye Bye, Birdie, which is fun but not Sondheim. But somehow, sung with that bravado and joy and excitement and underscored by that hot band, the lyrics spoke to me:

“… [T]here’s wine all ready for tasting / And there’s Cadillacs all shiny and new / Gotta move ’cause time is a-wastin’ / There’s such a lot of livin’ to do. / There’s music to play, places to go and people to see / Everything for you and me / Life’s a ball if only you know it / And it’s all waiting for you / You’re alive, so come on and show it / There’s such a lot of living to do.”

I heard it, and I believed it. I figured, hey, this slight man had a four-pack-a-day cigarette habit, a glass eye, grew up without his mom, had to deal with relentless racism from day one, and performed in hotels that he was barred from sleeping in because of the color of his skin (until he became a big name and helped break the color barrier in show business). And man, did he love life. He ate it up and went over the top, drinking and smoking and skirt-chasing, and hanging out with some unsavory folks, yes—but he also took a song like “Lush Life” and sang it like he’d lived it. He sang every song as if he lived it. And he meant every word.

He brought fun and swing and life into everything he sang. Sometimes the hipster kitsch of it was too much for me, and sometimes the low-brow, I’m-gonna-please-everybody style of his later years felt like he’d dumbed-down his act, especially considering what sophistication he was capable of. His desire to please everybody and be up, up, up all the time cheapened his rep in the eyes of many of us, but the joy he brought to life, the beauty he found in it and made for others.

That devotion to wringing every drop from it reminded me how lucky I was and how many wonderful things are around for me to enjoy. I thought it seemed a sin to waste another day in disappointment that I’m not doing more exciting work, and I vowed I’d make good things happen, find them, make sure they’re a part of every day of mine, and every one of my daughter’s days, too. I figured if Sammy, who had so much trash to contend with, could take his talent and shoot it off like fireworks, why can’t I take whatever gifts I have and make something fine and exciting of them, too? I may not be the dynamo Sammy was, but I don’t have his struggles either. And one doesn’t have to be a superstar to find something splendid in each day, or to make fine things happen.

So from that day forward I’ve reaffirmed my dedication to finding and doing good work, to making beauty, to learning something good and doing something kind each day, to being grateful for the opportunities to enjoy life more and to worry less about my dwindling savings (and how long it takes to find good jobs), and to writing regularly and with purpose. In a roundabout way, I have Sammy to thank for inspiring me to start this site. The wham of Sam, indeed.