[Revised from an article published on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

I recently purchased a cache of vintage magazines from 1960 to 1971, and have marveled at the extent to which the content, writing styles, focus of advertisers and willingness to talk candidly about social issues changed over the course of that decade.

The transition from the height of the Cold War in 1960 to U.S. immersion in a very unpopular war in Vietnam in 1971 is fascinating. During this period, women’s magazines changed more than they had in any other single decade since the Depression. In 1960 they were filled with home-centered fantasies and prescriptive articles telling how to be the ideal wife and mother with perfectly starched aprons, a fresh darling dress and matching heels, an adoring husband and well-fed children who loved your latest Jello creation. By 1971 they were covering serious, formerly unmentionable subjects like sexual problems, psychiatry and psychotherapy, rising drug use among youth, and other hot-button social issues and political stories that would never have made it into a women’s magazine a decade earlier. Of course, there were still articles with titles like “17 New Designer Patterns for Fall” and “The Foods that Make You Prettier.”

I was surprised to notice how many of the products advertised in 1960 would be found to be downright dangerous in the following ten to twenty years. The archetypal housewife of 1960 had the specter of The Bomb looming over her life and she was trying to use modern chemistry and technology to provide a cleaner, whiter, safer life for her family. How ironic, then, that these fresh technologies and newly synthesized chemical compounds would later be the cause of so much unnecessary suffering.

The oldest of the magazines is an issue of Good Housekeeping from May 1960. The very first page of the issue has an ad for Ipana toothpaste touting their new germ-killing ingredient, hexachlorophene. I remembered the brouhaha caused by hexachlorophene in the early seventies, when it was discovered that the potent germ killer, chemically related to herbicides, was toxic and could cause cerebral swelling and brain damage in humans. We had pHisoHex, a very popular facial cleanser incorporating hexachlorophene, in our home when I was a child. I remember when it and other affected products were pulled from the market with much alarming media coverage in 1973. The product is actually still sold and used to prep skin for surgery and fight infections that haven’t responded to other treatment, but packaging warns against excess hexachlorophene absorption and the possible dangers to the central nervous system.

I didn’t have to look far to find another dangerous product marketed to anxious mothers with sick children. Page 4 features an article for St. Joseph Aspirin for Children, a delicious treat I remember from my childhood. Tiny orange-flavored aspirin tablets for children were chewable and so tasty, the company had to invent child-proof caps (which I remember opening for my grandmother because she didn’t my childish dexterity). Kids ate them like candy. Of course, by the 1980s it was discovered that Reye’s syndrome, a severe illness which can cause acute encephalopathy, can be caused by giving aspirin to children. When this was understood and NSAIDs like Ibuprofen began to be recommended for children’s use in place of aspirin, the number of cases of Reye’s syndrome dropped dramatically across the country. Plough was a smart enough company to change their marketing for what had been called “baby aspirin” to take advantage of the discovery that small amounts of aspirin taken daily could help ward off strokes in older people with high blood pressure. The company now markets the same product to older people who don’t have the risk of contracting Reye’s disease that children have.

Though not an advertisement, I do have to give a shout-out to the column “Foods with a Foreign Flavor,” which featured “Three festive recipes from Colonial America,” which is, of course, completely contrary to the point of having a column about international foods. Best of all was the recipe for Maple-Nut Whip Pie, which included as a primary and necessary ingredient a package of unflavored gelatin, which, as you may know, wasn’t a product found in Colonial American kitchens. A whipped cream pie based on gelatin and egg whites whipped into a near meringue—no recipe could be more foreign to an early Colonial American.

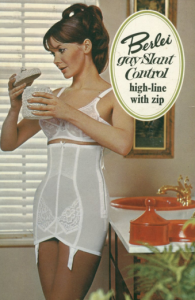

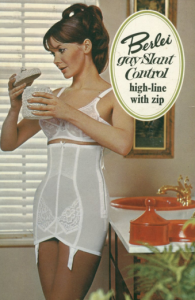

Warner’s, still a major maker of women’s undergarments, featured a lovely layout of mannequins wearing scary bras and girdles to keep women’s bodies completely jiggle-free. My favorite set? Probably the “Most famous Double-Play” high-topped girdle with built-in garters (remember, pantyhose hadn’t been invented yet) in the elegant blue pearl colorway, with “Matching pantie” and “A’Lure” bra. The ad exults, “Happy you! Your hunt-and-fret days of girdle choosing are over!” Each girdle offers some new fresh Hell of discomfort so that you might fit more snugly into that Jackie Kennedy-knock-off skirted suit made of fatteningly bumpy chenille that was so popular at the time. “Some with midriff-shaping Sta-Up-Top! Some with hip-slimming side panels; all with flattening back panels!” Because every woman wants a flat behind, right? Huh. This was an era when a natural wiggle was the sign of a loose woman, and a woman who wore a dress without a slip was an absolute hussy. The ad claims these products had “All-over slimming made magically comfortable,” but my mom’s girdles were tighter than compression bandages and lined in horrible rubber ridges. In hot weather, those ridges pressed deeply into her skin. There was little that was less magically comfortable than those horrid, tight, hot, constricting monstrosities. They were better than rib-crushing corsets, but a far cry from today’s comfy undies.

Berlei high-line girdle ad from the 1960s

The Equitable Life Insurance ad on Page 21 features a serious, carefully dressed woman in a kitchen doing deep knee-bends next to the stove while her husband and son sit at the kitchen table ignoring their cherry-topped grapefruit halves to ogle the hot mama who has kicked off her shoes and is earnestly working to keep her fine figure. It’s like a scene right out of “Mad Men,” set in the early 1960s in the Madison Avenue ad world, where a woman’s job was to get and keep a man, and where men taught boys to look at women, even mom, as objects of desire and little else.

Do you remember Fizzies, the tablets dropped into plain water than created instantly carbonated drinks? Kids loved them, and most of us tried to get our moms to let us have some to suck on without water so we could feel the effervescent action directly on our tongues. Page 24’s ad promises “Fizzies are FUN to make and drink—and so GOOD for you!” I had to wonder how they could make this claim about the “sprizzling, sparkling goodness” of their product, which was “as up-to-date as the newest jet.” It turns out “Mothers prefer Fizzies, too—they’re two-ways better for health. No sugar—safer for teeth—won’t destroy healthy appetites.” Hmm, no sugar? They wouldn’t be sweetened with saccharin, the earliest artificial sweetener, would they? My research confirmed that yes, they were. And saccharin was the focus of yet another health scare in the early 1970s; in fact, the USDA attempted to ban the substance in 1972, as another artificial sweetener, cyclamate had been banned in 1969 after causing bladder tumors and cancer in rats. Cyclamate had been used in an earlier formulation of Fizzies. Saccharin was and remains banned in Canada while remaining the third most popular artificial sweetener in the U.S.

The attractive opera star Roberta Peters is featured in two different ads in this issue, one for St. Joseph’s Aspirin, the other for Murine eye drops. It’s hard to imagine a mainstream magazine featuring a coloratura soprano diva to sell anything at all nowadays, the art form is so much less popular among the general public. Roberta Peters was a well-known figure then, not only on the stage but also on TV and radio. Even though the average American lived on modest means in a modest home or apartment with much less education than is normal now, there was a greater ease with an interest in classical vocal and orchestral music at the time. Leonard Bernstein‘s Young People’s Concerts featuring classical music interspersed with Bernstein’s captivating commentary were televised from Lincoln Center in New York City to the rest of the country for a decade beginning in 1962, and they were enormously popular, helping people of all ages to become conversant with the classical canon.

Skipping recipes for curried fruit bake and a jeweled Bavarian (a dessert that includes raspberry “gelatine,” port wine, eggs, scalded milk and heavy cream—ugh), I find an ad for Velveeta, the “pasteurized process cheese spread” of my childhood that seems to have been melted all over everything. There’s an exciting frost-free Frigidaire (and if you don’t think a frost-free freezer isn’t exciting, you’ve never defrosted an iced-over fridge and dealt with the resulting puddles on your floor). Another ad features a woman in pearls wearing a spotless white blouse and no apron while she cleans a filthy oven. Such fantasy. My favorite product name in this issue? That would be the cream deodorant with this straightforward moniker: ODO-RO-NO.

Hey, are you old enough to remember bad home perms? Girls whose moms had left the permanent wave solution on their heads so long they ended up looking like frizzed-out poodles? Here on page 153 is Bobbi, a home perm kit that you put in at night and don’t wash out until morning. Trying to sleep while wearing hard plastic perm curlers all night is one thing; having that horrible-smelling chemical stew sitting on your head for eight hours and breathing it in is another. On page 157 is Come Alive Gray, the hair color for women who like their gray hair. Add a brilliant pearly glow, enjoy a gleaming silver, or “add lustre . . . with rich, smoky tones.” I remember these different shades of gray on old ladies: lots of slightly lavender, blue or even pink hair was popular for a time, and these chic ladies sometimes dyed their poodles to match.

Bradley Cooper sports a head full of home permanent curlers in the film “American Hustle,” which takes place during the perm-crazy 1970s

Ah, doilies! I’d forgotten how popular they once were. Paper doilies under every cake, plastic doilies under Hummel figurines (because “Your ‘best’ looks better on plastic Roylies”), even crocheted lace doilies on backs of chairs to keep the hair oil off the furniture (that’s why they were called antimacassars—to keep the macassar men’s hair oil off the brocade). And Brillo pads! They were once so popular before nylon scrubber sponges came along to save us from quickly rusting soap-imbued metal mesh pads that stabbed one with loose, sharp aluminum points. By 1960, Brillo pads contained “Jeweler’s Polish” and produced a “richer, livelier lather.” Yes, lively soapsuds.

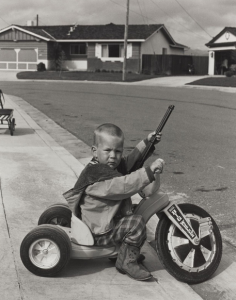

“Live Outside and Love It!” You can with Hudson pesticide sprayers and dusters. Wear your pretty spring dress and spray DDT all over your roses while your husband teaches your daughter to putt six feet away and your son sits at Dad’s feet, looking up adoringly. All of that is charmingly illustrated in Good Housekeeping. Of course, in 1960 gardeners had no idea that DDT was so extremely toxic that it would be banned in 1972, and so persistent that it still shows up regularly in the blood of people alive today. In the United States DDT was detected in almost all human blood samples tested by the Centers for Disease Control in 2005. It is still commonly detected in food samples tested by the FDA.

Make light work of chores indoors by playing your new miniature radio with six transistors. This tiny beauty is only four by six inches and costs just $39.95—that’s in 1960 dollars, when the average income of a four-person family was $5600 per year.

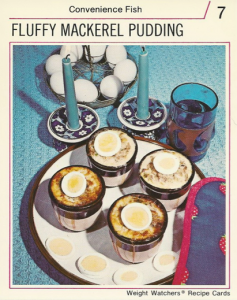

Isn’t it odd that not one but at least two tuna canners wanted to compare their tuna to chicken last century? I knew of Chicken of the Sea, but had you heard of Breast-O’-Chicken Tuna? And have you tasted Pretzel Meat Loaf? Yes, meat loaf made with the lavish inclusion of crushed pretzels, “catsup” and canned mushrooms. There’s a recipe on page 215 you won’t want to miss. (Urp.)

What other hazardous materials was advertised here? Well, there’s a baby powder that’s almost certainly made of talc, which contains asbestos and has been asserted to raise the risk of ovarian cancer in females who use it in the genital area. Nowadays pediatricians recommend avoiding talcum powder and suggest using powders with a cornstarch base instead. A few pages later is a hot steam vaporizer, the kind I scalded myself on numerous times as a kid. The glass got so hot, the steam burnt my fingers or legs as I neared it, and the whole thing had a rounded bottom so it could tip and spill nearly boiling water and hot liquid Vick’s Vapo-Rub (which was melted in the well on the top and sprayed into the air, leaving a fine petroleum-based film all over the windows and, it turns out, irritating the lungs as well). Thank goodness for today’s cool-air humidifiers.

Next page? Mothballs! Very toxic, made with naphthalene, they can cause all sorts of bad side effects with increased exposure, and can cause death when eaten. Why would you eat a mothball? Ask all the little kids who’ve tried them! A few pages later we find insect killer spray (very likely DDT-laced). Anxious about the hazards in this big, crazy world? Why not brighten up your home interiors with a coat or two of SatinTone paint? People of the Mad Men era used this (probably leaded) oil paint on the walls of baby’s rooms and the volatile vapors stunk up their homes and burn their throats for days before it finally dried. It’s hard to overstate how wonderful the invention of fast-drying, low-stink indoor acrylic paint is.

Honestly, this magazine is a minefield of health and safety disasters just waiting to happen. What a fascinating reminder of how much we’ve learned in the last fifty years about environmental toxins, hazardous home-based chemicals and healthy eating!