The melding of Dionne Warwick’s voice with songs by Burt Bacharach and Hal David was one of the loveliest things to happen to music in the 1960s. Like her younger cousin Whitney Houston, Miss Warwick had a natural elegance and seeming effortlessness to her performances that belied the skill and preparation behind her work. This serene stylishness was played up in studio recordings and TV appearances. In an exciting video of a very young star performing the hit “Walk on By” live in 1964, that cool grace is mixed with a freshness and verve that really makes me wish I’d seen her perform in person.

But we can still enjoy her wit—her Twitter feed shows that the superstar now affectionately known by many as “Auntie Dionne,” still has plenty of humor and joie de vivre to go around.

Tag Archives: 1960s

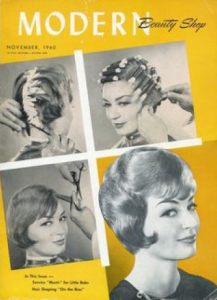

British Beauty Tips Circa 1960

In 1908, Pathé invented the newsreel, a short-subject film shown in cinemas prior to feature films. The Pathé Brothers of France owned the world’s largest film equipment and production company, and they saw the benefit of bringing news to life for moving picture fans and thus padding out an afternoon or evening’s cinematic entertainment. In the years before television, people grew to rely on newsreels during their weekly cinema visits to keep up with royal visits, war news, sports, fashion and celebrity events and travelogues that took them to far-away places.

Over time, many short subject films took on a nationalistic bent, and they were used as propaganda tools during World Wars I and II. Some showed women on the home front how to make do with rationed food and fabrics during and after World War II. Others showed teens at play, making them seem like laughable aliens, underscoring the generation gap that caused such rifts between teens and their parents in the 1950s and 1960s and played out in major culture clashes in both cinematic and real life.

News reels often depicted the people of other nations as quaint and exotic, and made women look like vain, silly, laughable lightweights. But they were wittily narrated, well-edited and often visually sumptuous, so they make for fascinating views into 20th century cultural history today.

Pathé short-subject films reached the height of their appeal in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s in Britain. Many of these shorts involve women being made to look foolish while demonstrating outlandish fashion or beauty trends and inventions, all accompanied by an orchestra playing a peppy tune and a wry male narrator making snappy sexist comments.

It’s always interesting to see how much effort has been put into inventing odd machinery to distract women, perpetuate stereotypes and keep women “in their place.” It still goes on today, of course, but now women’s voices are used to make the narrated hype more palatable and to seem more “empowering” and less demeaning.

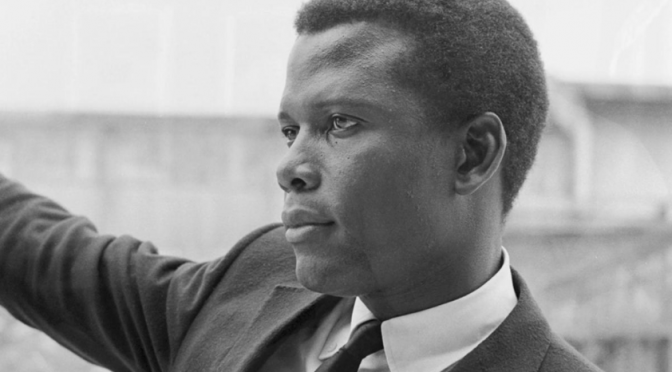

Sidney Poitier: Cinema’s Great Black Hope

Today film legend Sidney Poitier turns 92. I’ve never seen him give a bad performance, and I especially love him in To Sir, With Love, In the Heat of the Night and The Lilies of the Field, the last of which earned him an Oscar. He could have given extraordinary performances about any subjects, but Hollywood sought him out especially to help white audiences challenge their prejudices and rethink their unwitting racism.

Movie studios of the 1960s took the pulse of the culture and wanted to find a beautiful black man who seemed unimpeachably smart, brave, honest, talented and appealing—in short, a perfect black man—to make their characters come to life. But they got so much more. They got someone who felt real, natural, wise and good. There was no stiffness, no artifice, no arrogance. He was powerful, but not through violence—through reason, through integrity, through courage.

Poitier might have enjoyed having a chance at roles that didn’t always put his race front and center. But his talent, grace, insight, subtlety and decency allowed him to break through to people who seemed unreachably, permanently prejudiced at a time when America needed that more than anything. His performances were wonderful in their own right, but their influence on culture spread the importance of his characterizations far beyond the range of mere entertainment.

The performance that’s dearest to me of all of his work is not one of his tour-de-force performances like In the Heat of the Night—it’s his charming, naturalistic and deeply sympathetic performance in A Patch of Blue. The 1965 film is about a gentlemanly, intellectual and extremely kind man who befriends an abused, naïve and blind white teenager, the daughter of a trashy bigot, who has no idea that her best friend and mentor is a black man. The story sometimes gets a bit mawkish or obvious, and some of the other performances run a little over the top, but Poitier never does. As always, he gives it a quiet intensity, a sweet humor and a still, warm, humane focus.

This scene is one of the least dramatic in the film, but it shows perfectly how Poitier tells you everything you need to know about his character through his everyday expressions of humor and decency. It is in these small, perfect moments in each of his films that he becomes real, universal, a man we can all admire, a man we want in our own families. He could convincing play a friend, a romantic partner, an officer of the law, a builder of buildings and emotional bridges—someone we would all want in our lives. He was the honorable authority, the advisor, the father figure, a man who was always attractive and alluring but not overly sexualized, intense but not out of control. He was a black man who was both able and allowed to play an ideal man. And that changed everything.

The Boys in the Band

[In honor of the Broadway revival of Mart Crowley’s 50-year-old play The Boys in the Band starring Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, Matt Bomer and Andrew Rannells, I’m reposting this piece I wrote in 2009.]

Some years ago, while watching TV in the wee hours of the morning, I happened upon a film that I’d never before heard of. I was instantly hooked. It turned out to be a milestone in gay-themed filmmaking, a cult classic that alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) delighted and appalled New York theatrical audiences in 1968 and then moved to the screen in 1970. That film was The Boys in the Band.

Written by gay playwright Mart Crowley, the play attracted celebrities and the New York in-crowd nearly instantly after it opened at a small off-Broadway theater workshop in 1968. The cast of nine male characters worked together so successfully that the whole bunch of them made the transition to the screen in 1970, which is nearly unheard of.

Crowley had been a well-connected and respected but poor young writer when his play became a smash in 1968. While still a young man, he knew how the Hollywood game was played and how to jockey his success into control over the casting of the film. Working with producer Dominick Dunne he adapted his script into a screenplay and watched director William Friedkin, who also directed The French Connection and The Exorcist, lovingly keep the integrity of the play while opening it up and making it work on the screen.

It’s hard to believe that the play opened off-Broadway a year before the Stonewall riots that set off the modern-day gay rights movement in New York and then swept across the country. The characters in the play, and the whole play itself, are not incidentally gay—the characters’ behavior and the play’s content revolve around their homosexuality. For better or worse, the characters play out, argue over and bat around gay stereotypes: the drama queen, the ultra-effeminate “nelly” fairy, and the dimwitted cowboy hustler (a likely hommage to the cowboy gigolo Joe Buck in the 1965 novel Midnight Cowboy, which was made into a remarkable film by John Schlesinger in 1969). The play also features straight-seeming butch characters who can (and do) “pass” in the outside world, and a visitor to their world who may or may not be homosexual himself.

The action takes place at a birthday party attended only by gay men who let their hair down and camp it up with some very arch and witty dialog during the first third of the film, then the party is crashed by the married former college pal of Michael, the host. A pall settles over the festivities as Michael (played by musical theater star Kenneth Nelson) tries to hide the orientation of himself and his guests. That is, until the party crasher brings the bigotry of the straight world into the room, and Michael realizes he’s doing nobody any favors by keeping up the ruse. During the course of the evening he goes from someone who celebrates the superficial and who has spent all his time and money (and then some) on creating and maintaining a reputation and a public image, to a vindictive bully who lashes out at everyone and forces them all to scrutinize themselves with the same homophobic self-hatred he feels. He appears at first bold and unflinching in his insistence on brutal honesty, but he goes beyond honesty into verbal assault, while we see reserves of inner strength and dignity from characters we had underestimated earlier in the play. Though The Boys in the Band isn’t the masterpiece that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is, I see similarities between the two in the needling, bullying and name-calling that alternates with total vulnerability and unexpected tenderness.

The self-loathing, high-camp hijinks, withering bitchiness and open ogling made many audience members uncomfortable, a number of homosexuals among them. Some felt the story and the characterizations were embarrassingly over-the-top and stereotyped. They thought that having the outside straight world peek in and see these characters up close would only make them disdain homosexuals even more. This is a legitimate criticism; the nasty jibes, pointed attacks, and gay-baiting that goes on among and against gay characters here is the sort of in-fighting that could encourage bigots to become more entrenched in their prejudices when seen out of the context of a full panorama of daily life for these characters.

However, the play and film were also groundbreaking in their depictions of homosexuals as realistic, three-dimensional men with good sides and bad. Even as we watch one character try to eviscerate the others by pointing out stereotypically gay characteristics that make them appear weak and offensive to the straight world at large, there is also a great deal of sympathy and empathy shown among the characters under attack, and even towards the bully at times. Sometimes this tenderness is seen in the characters’ interactions. At other times, it is fostered in the hearts of the audience members by the playwright. Playwright Crowley has us witness people behaving badly, but we recognize over time how fear and society’s hatefulness toward them has brought them to this state.

These characters may try to hold each other up as objects of ridicule, but the strength of the dialog is that we in the audience don’t buy it; with each fresh insult, we see further into the tortured souls of those who do the insulting. We see how, as modern-day sex columnist Dan Savage put it so beautifully in an audio essay on the public radio show This American Life in 2002, it is the “sissies” who are the bravest ones among us, for they are the ones who will not hide who they are, no matter how much scorn, derision and hate they must face as a result of their refusal to back down and play society’s games. Similarly, to use another theatrical example, it is Arnold Epstein, the effeminate new recruit in the Neil Simon 1940’s-era boot-camp play Biloxi Blues, who shows the greatest spine and the strongest backbone in the barracks when he does not hide who he is, and he willingly takes whatever punishment he is given stoically and silently so as not to diminish his honesty and integrity or let down his brothers in arms.

The situation and premise of The Boys in the Band are heightened and the campy drama is elevated for the purposes of building suspense. This echoes the action in plays by Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill, where the uglier side of each character is spotlighted and the flattering gauze and filters over the lenses are stripped away dramatically as characters brawl and wail. The emotional breakdowns are overblown and the bitchy catcalling is nearly constant for much of the second half of the film, which becomes tiresome. However, the play addresses major concerns of gay American males of the 1960s head-on: social acceptability, fear of attacks by angry or threatened straight men, how to balance a desire to be a part of a family with a desire to be true to one’s nature, monogamy versus promiscuity, accepting oneself and others even if they act “gayer” or “straighter” than one is comfortable with, etc.

It is startling to remember that, at the time the play was produced, just appearing to be effeminate or spending time in the company of assumed homosexuals was enough to get a person arrested, beaten, jailed or thrown into a mental institution, locked out of his home or job, even lobotomized or given electroshock therapy in hopes of a “cure.” In 1969 the uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village by gay people fighting back against police oppression was a rallying cry. It gave homosexuals across the nation the strength to stand up for their rights and refuse to be beaten, threatened, intimidated, arrested or even killed just for being gay. However, anti-gay sentiment in retaliation for homosexuals coming out of the closet and forcing the heterosexual mainstream to acknowledge that there were gay people with inherent civil rights living among them also grew.

Cities like San Francisco, Miami, New York and L.A. became gay meccas that attracted thousands of young men and women, many of whom were more comfortable with their sexuality than the average closeted American homosexual and who wanted to live more openly as the people they really were. There was an air of celebration in heavily gay districts of these cities in the 1970s and early 1980s in the heady years before AIDS. It was a time when a week’s worth of antibiotics could fight off most STDs, and exploring and enjoying the sexual aspects of one’s homosexuality (because being a homosexual isn’t all about sex) didn’t amount to playing Russian Roulette with one’s immune system, as it seemed to be by the early to mid-1980s. Indeed, of the nine men in the cast of the play and the film, five of them (Kenneth Nelson, Leonard Frey, Frederick Combs, Keith Prentice and Robert La Tourneaux) died of AIDS-related causes. This was not uncommon among gay male theatrical professionals who came of age in or before the 1980s. The numbers of brilliant Broadway and Hollywood actors, singers, dancers, directors and choreographers attacked by AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s is staggering.

When the film was made in 1970, all of the actors were warned by agents and others in the industry that they were committing professional suicide by playing openly gay characters, and indeed, several were typecast and did lose work as a result of their courageous choices. Of those nine men in the cast, the one who played the most overtly effeminate, campy queen of all (and who stole the show with his remarkable and endearing performance) was Cliff Gorman. He was a married heterosexual who later won a Tony playing comedian Lenny Bruce in the play “Lenny,” which went on to star Dustin Hoffman in the film version. Gorman was regularly accosted and accused of being a closeted gay man on the streets of New York by both straight and gay people, so believable and memorable was his performance in The Boys in the Band.

The play is very much an ensemble piece; some actors have smaller and more thankless roles with less scenery chewing, but it is clear that it was considered a collaborative effort by the cast and director. The enormous mutual respect and comfort of the characters with each other enriched their performances and made the story resonate more with audiences than it would have otherwise. The actors saw the film and play as defining moments in their lives when they took a stand and came out (whether gay or straight) as being willing to associate themselves with gay issues by performing in such a celebrated (and among some, notorious) work of art. When one of the other actors in the play, Robert La Tourneaux, who played the cowboy gigolo, became ill with AIDS, Cliff Gorman and his wife took La Tourneaux in and looked after him in his last days.

In featurettes about the making of the play and the film on the newly released DVD of the movie, affection and camaraderie among cast members are evident, as is a great respect for them by director William Friedkin. Those still alive to talk about it regard the show and the ensemble with great love. As Vito Russo noted in The Celluloid Closet, a fascinating documentary on gays in Hollywood which is sometimes available for streaming on Netflix, The Boys in the Band offered “the best and most potent argument for gay liberation ever offered in a popular art form.”

According to Wikipedia, “Critical reaction was, for the most part, cautiously favorable. Variety said it ‘drags’ but thought it had ‘perverse interest.’ Time described it as a ‘humane, moving picture.’ The Los Angeles Times praised it as ‘unquestionably a milestone,’ but ironically refused to run its ads. Among the major critics, Pauline Kael, who disliked Friedkin and panned everything he made, was alone in finding absolutely nothing redeeming about it. She also never hesitated to use the word ‘fag’ in her writings about the film and its characters.”

Wikipedia goes on to say, “Vincent Canby of the New York Times observed, ‘There is something basically unpleasant . . . about a play that seems to have been created in an inspiration of love-hate and that finally does nothing more than exploit its (I assume) sincerely conceived stereotypes.'”

“In a San Francisco Chronicle review of a 1999 revival of the film, Edward Guthmann recalled, ‘By the time Boys was released in 1970 . . . it had already earned among gays the stain of Uncle Tomism.’ He called it ‘a genuine period piece but one that still has the power to sting. In one sense it’s aged surprisingly little — the language and physical gestures of camp are largely the same — but in the attitudes of its characters, and their self-lacerating vision of themselves, it belongs to another time. And that’s a good thing.'” Indeed it is.

[Originally published in June 2009.]

Eight Days a Week: On Tour with The Beatles

Tonight I indulged in an evening of nostalgia inspired by a viewing of Eight Days a Week: The Touring Years, the satisfying and enjoyable new documentary about directed by Ron Howard. Though no one can doubt Howard’s ability to present stories with energy and enthusiasm, I have often found his films too mawkish and obvious for my taste. Happily, it turns out he has a knack for creating a crackerjack musical documentary. He’s put together a jaunty but detail-rich story with the full cooperation of (and incorporating recent interviews with) living Beatles Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr, and with help from the widows of John Lennon and George Harrison.

Growing up during the 1960s and being steeped in Beatles music from birth, as I was, I have always seen The Beatles as my band and my musical family members, and I’ve viewed their music as a personal treasure that I just happen to share with the world. This film brings back the best moments of my childhood, reminds me of just how fresh and delicious their music was (and still is today). This documentary is a bright, shiny reminder that no, their power, talent and influence haven’t been overblown: they really were that good and that important to world culture in the 1960s. There was an open lightheartedness and sincerity about them which this documentary displays lovingly, but without treacly reverence or false heroism. They were a force to be reckoned with, but what they wanted most of all was not to be legends to millions of young girls or to worry about what their cultural legacy would be years hence; they just wanted to create really great music and bring joy. And they did.

As meaningful as my own relationship with The Beatles’ music feels to me, I know that I share my all-time-favorite band with a literal billion other people who love them, too, and this film makes that clear: the enormity of Beatlemania, the record-breaking crowds that showed up to see them, hurled themselves into fences and onto stages, and even broke through doors and windows to get to them are all on display here. But the nature of The Beatles’ electrifying and original music, as well as their enormous personal charisma and warm connection to each other and to their fans, is that we feel an intimate connection to them and to their music. After all, their songs have been part of our personal soundtracks for over a half-century. This film makes their charisma, their discipline and their energy feel fresh and palpable, and the large amounts of color footage and clever use of still photos and black-and-white film, along with surprisingly well restored audio tracks, makes them feel breathtakingly contemporary.

The Beatles were joyful, bracingly honest, and so cheerfully rowdy that they turned all stereotypes of British primness upside-down. They were also egalitarian, working class and, when it came to race, colorblind. In Eight Days a Week, Whoopi Goldberg, who has been a huge Beatles fan since childhood and who saw them at Shea Stadium when she was a girl, says in this film that when she saw and heard The Beatles, she felt like they were her friends, that their music spoke to her, that she didn’t feel like an outsider when she played their records. She felt like they would welcome her into their world if they knew her, which was unusual and deeply touching for a young black girl to feel about a group of white English guys in 1965. And she was right; when they went to the South, they were told they could only perform to segregated audiences, and they refused. They put an antisegregation rider into their contract, and once they broke the color barrier at their concerts, those stadium concert venues stayed desegregated for other performers who came after them. When they decided to augment their recordings with an outside keyboardist near the end of the band’s life, they chose megatalented black funk star Billy Preston to play keyboard for them, creating those iconic keyboard solos in songs like “Get Back.” You can see Preston, who was the only non-Beatle ever credited for performing on any of their albums, performing with them at the end of the film as they played their last-ever live concert together on the top of their office building, as can be seen in the concert film made of their final album together, Let It Be.

Those of us who were born in the 1960s grew up with Beatles music being a constant presence in our lives, and we who were most deeply touched by them can still sing dozens, even hundreds of their songs by heart, so catchy and fresh and powerful were their tunes, their lyrics and their arrangements. (And the documentary makes clear that they owed a great debt of gratitude to producer George Martin, who died this year and to whom the documentary is dedicated.)

To the people of the United States who were introduced to the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show and on the radio in early 1964, The Beatles seemed to come out of nowhere and to be overnight sensations. Of course, we all know now that they’d spent years honing their craft in the underground bar in which they were discovered in Liverpool, The Cavern, and in the seediest nightclubs of Hamburg, Germany, where they polished their performance skills, practiced and performed for up to eight hours a day, and all slept in one room together with their shared bathroom down the hall, like brothers. By the time they came to the U.S., they saw each other as brothers, as the film makes clear.

The overwhelming, relentless, exhausting quality of their life on the road is displayed and narrated by The Beatles themselves in this film, but their resilience, wit, energy and powerful loyalty to each other are also evident. The excellent footage and recordings, some only discovered recently after the filmmakers put a call out to Beatles fans via social media, are masterfully arranged and edited, and despite the extremely public nature of their lives and careers, the film feels quite intimate at times.

Ron Howard is known for being somewhat obvious and superficial in the way he treats historical subjects, and that holds true here: there are few, if any, surprising facts or original insights in this film, though hearing Paul and Ringo (and George and John, in long-ago interviews) recount their stories with some pleasure is a treat. In Eight Days a Week, Howard does what he is particularly good at, and that is creating an energetic, buoyant piece of visually attractive entertainment (with enormous help from talented editor Paul Crowder) that feels immediate and real, and that leaves the audience feeling hopeful. I saw it with a full house of people aged 18 to about 80, and the college-aged people laughed at and delighted in the Beatles’ talents and antics at least as much as those of us who have been listening to Beatles music for 50 years or more. The college students in the audience were the first to break into applause at the film’s end.

If you love The Beatles as I do, make sure to stay seated throughout the end credits so you don’t miss the huge bonus at the end of the film: a newly restored, half-hour-long edited-down version of their 1965 concert at New York’s Shea Stadium, which was at that time the largest rock concert in history. Their fan base was so enormous, and the risk to safety from the huge gatherings of fans was so great, that their U.S. tours eventually had to take place only in giant stadiums. Indeed, police forces across the U.S. were regularly overwhelmed when The Beatles came to their cities, so unprecedented were their appeal and the enormity of the crowds they attracted.

During the Shea Stadium concert Paul and Ringo say they couldn’t hear a thing over the deafening noise of the crowd; Ringo had to stay in sync with Paul and John by watching them for visual cues, primarily by watching their hips. Concert footage shows what enormous stamina and determination were necessary to perform on that scale and at that pace for years on end. Every day meant hours of being rushed through hordes of screaming fans who were trying to bash in their car windows; being dragged around to photo shoots or film sets; being grilled by reporters; having perhaps 90 minutes at a studio with George Martin to test out a just-written song and bring it to full fruition on tape; and then going off to play a concert. The lack of private time was wearying. In between all the very public appearances, they would often be stuck together in a hotel room to avoid having their hair snipped and clothes ripped away by mobs of fans should they go out in public. This film shows the weariness and joylessness that this kind of life ultimately elicited, and makes clear why they decided to stop touring in 1966 and spend all of their remaining energy writing and recording rather than touring for their final five albums together.

While my lifelong love of The Beatles keeps me from being impartial in evaluating this new documentary, I can say that I felt it captured their spirit, freshness, talent and liveliness in a more visceral and emotionally stirring way than any other documentary I’ve seen about the band, and that I’ll be able to hear and enjoy their music in a deeper and even more appreciative way as a result. Many thanks to Paul and Ringo and Ron Howard for making this lively, lovely appreciation of The Beatles’ early years possible.

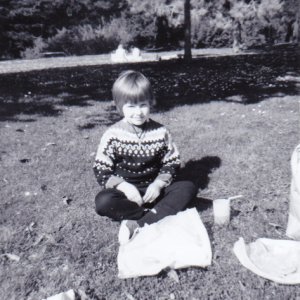

Child of the Sixties

The author in Golden Gate Park in the late 1960s

Among my childhood photo albums are pictures of me wearing daisy chains and sitting on the grass in Golden Gate Park. I have vivid memories of spending time with my father and his friends in the park and in the adjoining Haight-Ashbury district when I was a very little girl. I was tiny, but I remember San Francisco, the epicenter of the hippie movement, during 1967’s legendary Summer of Love and in the years thereafter.

Though I grew up in the suburbs, I often visited what people in the Bay Area refer to simply as The City. All my life I have felt a special pride in my connection to San Francisco. My mom gave birth to me there, in a hospital just a few blocks’ walk from the famous intersection of Haight and Ashbury Streets. My dad (whom I only lived with for the first few months of my life, and only saw occasionally from babyhood onward) brought me to various hippie happenings there during his visits with me from the time I was about three years old. He hoped to make up for what he saw as the soulless bourgeois childhood I was supposedly experiencing in the Bay Area’s eastern suburbs.

The PBS American Experience documentary on the Summer of Love shows a San Francisco very much as I remember it during that time, albeit from about three feet off the ground. As a young child, I found San Francisco’s hippies often scary and off-putting. Even as a very little girl I had a sense of the importance of personal space and a desire that things be done safely, with purpose and according to plan. I was much more of a cautious goody-goody than even my mother, a high school teacher whom my father denigrated for being too suburban. I followed rules; my father and his friends generally did not. My dad hated authority, rules and The Man, so he and his friends would take joy in challenging the establishment whether or not I was with them.

I was always the only child present on visits with my father, and was usually ignored, so I spent a lot of time in watchful anxiousness, hoping not to be put in harm’s way. I was frightened by his and his hippie friends’ lack of concern with their actions or with me; they were lackadaisical, careless, loudly vulgar and sometimes stoned, so I felt ill at ease and unprotected with them.

People often talk about how loving and peaceful hippies were, but I saw also an enormous amount of anger directed by them toward rules, history and authority. That anti-establishment anger was often channeled for good in such campaigns as the fight for full and equal rights for African-Americans, women, Native Americans and homosexuals, among other downtrodden groups. The often strident and unpleasant but necessary challenges to the entrenched establishment gave young people in particular the courage to question the wisdom of their leaders and force their government to justify its wars. They gave the populace the courage to stand against unjust laws and corrupt political practices. It was this movement that eventually gave journalists the courage and necessary establishment backing to bring down a powerful sitting president during the Watergate scandal just a few years later.

While the nation often benefited from the outspoken challenges of those who had felt stifled by government, big business and the limiting social mores left over from the 1950s, there was also an upsurge in more generalized antisocial behavior. The rise of the hippies led not only to social activism, peace and love, but also to huge numbers of (mostly) young people breaking rules just for the hell of it. Many wrapped their destructive or selfish behavior in a cloak of righteousness. Some took advantage of the new social openness to examine their psyches and motivations honestly and to try to relate to others in more direct and healthy ways; others just found this newly socially acceptable preoccupation with self an excuse for narcissistic behavior.

The ensuing decade of the 1970s was dubbed “The Me Decade” with reason. During the 1960s, modesty had lost favor while self-regard and constant awareness of one’s own needs and desires became viewed as positive things. Exuberant self-expression and in-your-face sexuality went from being shocking in the early 1960s to being surprisingly common within a decade. In the early 1970s, when I visited the high school where my mother taught (and which I would later attend), obvious bralessness was very common not only among the students but even among teachers. Some of the younger teachers wore hot pants to school. Overt sexuality was, however, considerably less evident in high school teachers’ fashions by the time I myself entered high school later in the seventies.

To be fair to those who were part of the laissez-faire San Francisco hippie culture of the 1960s, I saw plenty of self-absorption and self-aggrandizement even among more establishmentarian suburbanites during that time and in the decade that followed. Social boundaries were not well respected in general in the late 1960s; millions of people (not just hippies) were sharing their formerly private thoughts (not to mention their bodies and lots of adult-themed talk and media) with great abandon and carelessness, and we kids were often exposed to too much knowledge too soon. Those of us who appreciated having some boundaries in our lives were often ignored or denigrated by people who felt superior because of their mod, carefree sensibilities. Some, like my father, mistook the desires of others (like his young daughter) to follow laws, keep order or avoid conflict or offense as being necessarily conservative traits. They are not.

There was a middle ground in which people challenged the status quo more gently; they didn’t want social anarchy but still believed strongly in the promise of liberalism. Yes, many San Franciscans, hippies included, sought peaceful, meaningful, respectful social change and worked hard for it. But from my own perspective, as a very young person, I saw measured, realistic and inclusive social activism in the suburbs, too, even among those whom my dad and his friends found so hopelessly square.

The Free Design: Silky in a Sunny Sky

In the 1960s popular music went in a number of different directions. One cheerful subgenre of pop that originated in the U.S. was known as “sunshine pop” (or sometimes “flower pop” or “twee pop”) and was characterized by intricate vocal harmonies, sophisticated production (think of the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds” album) and upbeat warmth. In addition to the Beach Boys, some of the most popular sunshine pop bands were The Turtles (“Happy Together“), The Mamas and the Papas (“Monday, Monday“), The Fifth Dimension (“Up, Up and Away“), Harpers Bizarre (“Feelin’ Groovy“), Spanky and our Gang (“Lazy Day“), The Seekers (“Georgy Girl“) and the Association (“Windy“). A New York-based sunshine pop group of brothers and sisters called The Free Design was never as prominent as most of these bands, but they were among my favorite groups as a child, and I spent hundreds of hours listening to their albums. They were popular with professional musicians like my mother and her friends because The Free Design‘s musicianship was so strong and their compositions were often rigorous and showed evidence of classical training and technique.

Over the past decade, the music of The Free Design has seen a renaissance. One of their songs, “Love You,” appears regularly in a wonderful current ad for Delta Airlines, and has appeared in international ads for Toyota, in the charming Will Ferrell fantasy Stranger Than Fiction and as part of Showtime’s series Weeds. The syrupy sweet, lighter-than-air lyrics of “Love You” are as insubstantial as down and just as soft and appealing—here’s a sample:

Dandelion, milkweed, silky in a sunny sky

Reach out and hitch a ride and float on by

Balloons down below catching colors of the rainbow

Red, blue and yellow green, I love you

Weeds also featured the group’s song “I Found Love,” which was played on The Gilmore Girls as well. Nearly a half century after they first began recording, the group is delighting a whole new generation as part of a sunshine pop revival.

Some classify The Free Design as a “baroque pop” group since they incorporated intricate vocal harmonies and classical elements in their compositions, and they sang some melancholic ballads along with their uptempo hits such as “Kites Are Fun.” Some of their most beautiful songs, such as the heartbreakingly pretty “Don’t Turn Away” and the elegant but cynical song “The Proper Ornaments,” have a darker quality to them, and they expand into surprisingly complex vocal harmonies that certainly take them out of the sunshine pop mainstream and put them into the baroque camp. A terrific example of both their upbeat major-key sunshine pop sound and the baroque complexity of their interlacing close vocal harmonies is their song “Umbrellas.”

Their lovely but strange song “Daniel Dolphin” is an odd mixture of styles, upbeat seeming at first yet in a minor key, and while it begins as a song about a playful dolphin, it grows serious as Daniel carries away a dying old man. When Daniel returns, he is killed by those who misunderstand the reason for his journey, which turns out to have been to facilitate the old man’s reincarnation—a surprisingly arcane and dark twist from a group often mistakenly characterized as nothing but sunny.

The Free Design began as a trio of members of the Dedrick family: Chris, who wrote most of their songs, his brother Bruce and their sister Sandra. Their younger sisters Ellen and Stefanie joined the group later, but it is Sandy’s warm lead vocals that were at the heart of the group. Sandra Dedrick now lives in Ontario, Canada, where she writes poetry, songs and children’s books.

Only the Shadows of Their Eyes

I just watched the last 15 minutes of Midnight Cowboy, a movie I have admired for decades and seen a half-dozen times, but which brings me pain each time I watch it. It’s one of those films that I cannot turn away from if I happen to run across it while changing channels, so powerful are the performances and so unflinching is the focus on captivating yet repellent characters.

Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight are natural, believable and awkwardly honest in their roles (which are among the finest performances of their careers); John Schlesinger‘s direction is unflinching and powerful. Schlesinger was unwilling to turn away from the sorts of intimate, painful moments that other directors tend to cut away from in order to soothe audiences and tie up loose ends. He avoided palliative measures, trusting his audiences to handle the pain and unfairness at the heart of his characters’ worlds and sit with their devastation and disappointment even as the final credits rolled by.

The film begins with what sounds superficially like an upbeat tune with an ambling gait, the song “Everybody’s Talkin‘” sung by Harry Nilsson. The song, which won a Grammy and was a million-selling single in 1969, is deceptive; listen to the lyrics and you’ll see it’s about an overwhelmed man who can’t handle or comprehend the needs and conversations of the people around him and longs to move far away to a place without cares, “somewhere where the weather suits my clothes.” He sings:

Everybody’s talking at me

I don’t hear a word they’re sayin’

Only the echoes of my mind

People stopping, staring

I can’t see their faces

Only the shadows of their eyes

It’s easy for the casual listener to notice only the upbeat qualities of the song and the positive fantasies of the young man as he imagines himself moving lightly through the better life that awaits him:

Banking off of the northeast winds

Sailing on a summer breeze

And skipping over the ocean like a stone

The song suits the story of handsome but none-too-bright young Texan Joe Buck (played by Jon Voight) who leaves Texas in a hurry and moves to New York convinced that he’ll be a big success as a gigolo wearing his cowboy hat, boots and pretty-boy grin, and as he walks around Times Square in his fringed leather jacket he seems to be just a sweet, overgrown, oversexed kid. And he is, at first. Full of hope and confidence but leaving a disturbing and misunderstood past, he soon becomes overwhelmed like the man in the song. He longs to escape his life, first running to New York, then to Florida with his friend Rico (played by Dustin Hoffman). But in this story, there is no easy, rambling way through life or around trouble, and there’s no way for Joe to stop the cascade of horrible lessons that come with being too trusting, hopeful and needy while living among broken, wary people.

Midnight Cowboy is an exceptional film which captures the disturbing power of the fine novel by Leo James Herlihy upon which it’s based. Indeed, the movie, the only X-rated Best Picture Oscar winner ever, was a huge critical success despite its reputation for grim, mature subject matter, and it won Oscars for best picture and best direction. While the story is gritty, it isn’t by any means pornographic; the X rating was misleading. But the story is adult in nature, ultimately cynical, tragic and hopeless. The main characters are hustlers, professional liars at the bottom of society who are not very bright and are willing to take advantage of people in pain. Yet the story is told in such a way that, although we cringe when the principal characters harm themselves and others, we cannot help but feel our own hearts break as we watch their hopes go down in flames.

So why do I come back to this film, and why do I love other devastating Schlesinger films about unrequited love and loss (like his beautiful, faithful adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd and the 1971 drama Sunday Bloody Sunday with its exquisite performances by Peter Finch and Glenda Jackson) and of moral decay (like Marathon Man) so much? I suppose it’s because Schlesinger was a masterful storyteller who managed to focus on difficult, broken and fearful people, people on the edges of society, people who are willing to live in shadows. He let us watch them lash out at others in desperation, flail and grasp for meaningful connection with other people, and then have to live with their losses and failures. There are few redemptions in Schlesinger’s stories, but there is great humanity. Schlesinger helped viewers get under the skin of his characters and understand their pain without whitewashing their behaviors or putting them on pedestals. He loved flawed people and stories full of heartache, and he made a career of getting the intelligentsia to peer more closely at and care for stories about the very people those same people might cross the street to avoid in their daily lives.

Schlesinger, who was gay, incorporated homosexual themes into several of his films and teleplays, sometimes portraying gay men as self-loathing (as he did in a disturbing scene in Midnight Cowboy) but also including one of the first depictions of a successful, honorable, well-adjusted professional homosexual man in modern cinema (in Sunday Bloody Sunday). He treated his characters’ sexuality with the same straightforwardness he showed toward their other characteristics; it was simply another facet of their lives. This matter-of-factness, which made Sunday Bloody Sunday particularly advanced for its time, was part of a wave of naturalism in film also seen in the work of other important directors of the sixties and seventies such as Martin Scorsese, Mike Nichols, Tony Richardson, Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet and Peter Bogdanovich.

It may seem odd that some human beings (like me) seek out stories of loss, failure and emotional pain like this one both as forms of entertainment and as cathartic experiences. Such films shine a light on the human condition and help viewers like me to understand and empathize with the misbegotten and seemingly cursed people of the world in a way that feels especially visceral and real. Films like Schlesinger’s are, however, at enough of a remove that film lovers who appreciate a good dose of angst with their drama can feel safe sidling up to the misfits, losers and dangerous people who inhabit the underworld that Schlesinger created. There’s a voyeuristic thrill at getting so close to the people and emotions that scare or excite us, followed by a shock when we realize how close they are to ourselves.

The Birth of the Monkees

In 1965 Americans Micky Dolenz, Michael Nesmith and Peter Tork and Englishman Davy Jones were chosen to star in a TV show about an imaginary rock band inspired by the Beatles: they became The Monkees. Micky Dolenz came from a show-biz family, Mike Nesmith’s mother invented Liquid Paper (no kidding) and Davy Jones had earned a Tony nomination for his role as the Artful Dodger in the original Broadway cast of the musical “Oliver!” (He originated the role in the London cast.) Talented musician Stephen Stills (who later earned fame with Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills and Nash) had auditioned for the show but was turned down because his hair and teeth were deemed unsuitable during his screen test. When asked if he knew of another musician with a good “open, Nordic look,” he recommended his friend Peter Tork. From 1966 to 1968 the popular show featured the four young men in endless ridiculous scenarios and scores of musical performances. While considered by many to be a lightweight, manufactured ripoff of actual rock groups, the Monkees’ were actually talented musicians with real charm and their music was hugely popular: they sold more than 75 million records worldwide. After their show was canceled in 1968 they went on to release music for two more years and they had numerous successful reunion tours. At their peak in 1967, the band outsold the Beatles and the Rolling Stones combined. This compilation of their screen tests shows how fresh and young, boyish and goofy they were, but also shows the confidence and charisma each one displayed well before becoming big TV stars.

Low-Key Lustre, Elegant Beyond Price: Women’s Magazines of the Sixties

[Revised from an article originally published in Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

I recently purchased a great selection of vintage magazines dated from 1960 to 1971 and I’ve been enjoying stepping into the past each time I sit down to read them. My latest vintage magazine adventure has been with the June 1966 issue of McCall’s, the long-running popular women’s magazine. It’s been fun to compare it to the Good Housekeeping magazine from 1960 I wrote about a few weeks ago. In just that six-year span, the advertising copy grew much more florid, less concerned with keeping a perfect household and more concerned with personal sex appeal. I don’t know if it was the popularization of the birth control pill in the early 1960s that caused the subsequent cultural obsession with sexiness that sprouted in the 1960s and 1970s (as many social historians suggest), but the move from wanting a sparkling oven and a perfect meatloaf for one’s husband and children to the quest for bouncier hair, more luxurious nails and more kissable lips for an unnamed man is quite pronounced.

I love the over-the-top ad copy: “Suddenly everyone’s all eyes (and sighs!) over [Max Factor] Shadow Creme. The new glowy-eyed eye shadow that slips on like a dream, because it’s cream!” Adjectives morph into ad-copy-ready verbs to try to add youth and vigor to a phrase: with dreamy creamy eye shadow one can “sleek on a shy narrow line of color.” Or how about the nail polish which will apparently change your life with its heart-stopping, eye-catching beauty? You don’t just brush it on, you slither it on. Not slather, slither: one must apply it sexily, with the thrilling undulations of a snake. Yes, with Revlon Crystalline Nail Enamel, “Even before you slither it on, you’ll see the big difference. . . . On your nails it glows with a soft, low-key lustre. A quiet kind of chic. You’ll be smitten with the deep, velvety quality of it. The plushness. The cover. The delicate—but definite—color. Elegant beyond price.” I’m practically having palpitations just thinking of it.

Not getting enough action, you brown-haired beauties? The problem is with your makeup: you need Clairol Flicker Stick. “This is only for the brunettes who rather enjoy having their hair mussed occasionally. The very first lip gloss for Brunettes Only. Give your lips a lick of something new.” That’s wildly suggestive compared to the ads of 1960 and before. Another rather bold ad features a photo of a man in a business suit with his head and one hand both cropped away and his other hand holding a telephone. The focus of the photo is the man’s crotch, which is shown splay-legged sitting on an office chair. The headline? “If your husband doesn’t lift anything heavier than a telephone, why does he need Jockey support?”

The ad goes on to say that “During a normal day, a man makes a thousand moves that can put sudden strain on areas that require male support. Climbing stairs. Running to catch a bus. Bending. Reaching. Simple things, yet they are the very reasons why every man needs the support and protection that only Jockey brand briefs are designed to provide.” Otherwise, what, he might get a wedgie? Or lose his ability to sire a child because he ran up the stairs too fast? They seem to imply that his very manhood is in peril should he wear the wrong underpants.

The fashion emphasis by 1966 is on younger, fresher, livelier styles. The concern isn’t so much about using the latest and greatest (and shortly-thereafter-to-be-determined dangerous) drugs, pesticides and cleaning agents around the house in an effort to be more chemically controlled and germ-free, as had been so popular in 1960. By 1966 there was more of a desire to spend money and time on disposable products that made living more convenient and fun. The hedonism index rises dramatically during the 1960s, and there’s more of a desire to consume new, specialized products and live for today without concern for the cost or waste involved. There’s definitely a keeping-up-with-the-Joneses kind of jonesing for the latest, hippest disposable new thing.

For example, paper napkins and towels and coordinating tissues and became popular, and having one’s scented, dyed toilet paper match one’s scented, dyed facial tissues was a must. Ads offered bright, bold bath towels with garish flower power colors and patterns, then showed coordinating Lady Scott bathroom and facial tissue with colored flowers printed onto the paper in Bluebell Blue, Camellia Pink, Fern Green and Antique Gold. It’s a “color explosion in towels and napkins.” “Pop! go the colors of Scotkins—newly pepped-up to bring zing to table settings” and “gay bordered towels.” Don’t forget to “Scheme your tables with the vibrant new designs in the first cushioned paper placemats by Scott.” Scheme your tables?

Best of all, “Color explosion flashes into fashion with the paper dress!” For $1 plus a 25 cent handling fee you could buy a paper shift dress in a red and white bandana print or a black and white op-art geometric design. Original “Paper-Caper” dresses, still folded in their original envelopes, are now quite collectible; one of the bandana print was recently available on eBay for $25; another auction house is asking $150 for the op-art version. “Dashingly different at dances or perfectly packaged at picnics. Won’t last forever . . . who cares! Wear it for kicks—then give it the air.” Campbell’s soup cashed in on the disposable dress craze while demonstrating their pop art cred: they sold their own Andy Warhol-inspired paper “Souper Dress” printed with images of Campbell’s soup cans. Each sold for $1 plus two Campbell’s Soup labels in the sixties. Want one now? Ebay recently listed one with a starting price of $749; it sold for $1,125. Missed out on that one? Don’t worry; another has been listed for sale for $2,000.

Paper dresses were available in very simple styles, which were much like most fabric dresses of the day. Most women did at least some home sewing in an effort to economize, and almost all girls were taught to sew and cook in school, so essential were those skills deemed for females of the day. Many dresses were shapeless, boxy shifts, easy for any home sewer to whip up with a pattern bought at the nearest department store. My mother, an accomplished seamstress and knitter, never stopped with simple shifts; she made me wonderful pintucked blouses, perfectly tailored little coats, intricately cable-knitted sweaters and lovely dresses. We spent many happy hours in all the department stores’ sewing sections from as far back as I can remember. We visited the fabric departments of five-and-dimes like TG&Y (which was affectionately nicknamed “Toys, Garbage and Yardage”), popular stores like Mervyn’s and Penney’s, and slightly tonier establishments like the Bay Area’s Emporium-Capwell stores. Every good department store had a fabric section with a wide variety of materials, notions and patterns. Nowadays it’s hard to find fabric stores that aren’t superstore fabric-and-craft chains, and sewing is a niche market attended to by specialty stores only.

I don’t mean to get too personal, but do you remember spray deodorant? Wet and smelly, it got all over everything, spewed fluorocarbons into the air and ended up wasting a lot of product due to overspray, but it was oh, so popular in the sixties and seventies. But how do you market something like that to women? Like this: “Slim, trim, utterly feminine, hardly bitter than your hand . . . new cosmetic RIGHT GUARD in the compact container created just for you.” “Elegant . . . easy to hold, Right Guard is always the perfect personal deodorant because nothing touches you but the spray itself.” What a prissy little product, huh? And for those not-so-fresh moments that can’t be discussed in polite company, there was Quest, “a deodorant only for women.” It was a powder that “makes girdles easier to slip into,” among other things.

Having a separate female version of a product with prettier packaging was very popular: all sorts of spray cans and discreet boxes featured what looked like miniature wallpaper designs, floral themes and delicately drawn feminine profiles of wispy women who appeared unaware that they were being watched while they sniffed daisies (which are rather stinky flowers, actually).

I wish I could still send a quarter to Kotex for the fact-packed booklet titled “Tampons for Moderns.” One can only imagine the bouncy, well-groomed young women in the line drawings that must have illustrated the booklet, which I see in my mind’s eye as having a turquoise cover bearing a confident-looking brunette wearing a fresh white dress. (Such products are often advertised by women in white to emphasize their fresh, clean, pure quality and the idea that you won’t be the unclean mess you’ve been made to think you are if you’ll just use their products.) The booklet must have read a lot like the brochures and booklets I got at school during the seventies, full of “gee, it’s great to be a woman!” ad copy that played up the ease with which one could stay well-groomed, pretty and presentable even when afflicted by the horror of the condition that could barely be hinted at but which every female experienced. A “really, it’s not so bad!” tone lay behind every phrase and the subtle instructional nature of each conversational paragraph was supposed to allay concerns. I think it actually emphasized the unmentionable quality of the subject matter: this stuff is so important and secret, the text implied, you need official instruction books to deal with what every woman from time immemorial has gone through—but we still can’t address any of it head-on.

Before reading this magazine I’d forgotten just how popular hairpieces were in the sixties. They were quite common accessories and supplemented many women’s wardrobes, often with rather ridiculous results. Remember, many women still went to the hairdresser for weekly perms, blow-outs, cuts and curls and slept with their hair in hard plastic or itchy metal-and-nylon brush curlers or pincurls every night, spraying their coifs afresh with new coats of sticky Aqua Net hairspray each morning and avoiding washing their hair for as long as possible between beauty parlor visits. Adding fluffy, braided, curly, straight or poufy switches, falls or wiglets (don’t you love that word?) to the mix wasn’t a big stretch. Long hairpieces, braided or twisted, or fluffy poufs added onto the top or back of a hairdo weren’t uncommon; teasing hair up into domes, small head hillocks or B-52-large beehive cones was a regular thing. I remember women with hair that rose a good four to six inches above their heads and never moved, no matter what the weather did. Women only entered swimming pools without bathing caps in movies; public pools wouldn’t allow a woman or girl to swim unless a rubber cap, often covered in ridiculous colored rubber “petals” that came off and floated in the water, completely covered her head.

Of course, a women’s magazine couldn’t be simply about making oneself prettier for one’s man. A good housewife also had to feed him (using lots of prepared food products) and heat or chill the leftovers in appliances that came in sexy new colors and promised easy-care features. The Admiral Duplex Freezer/Refrigerator ad features eight—count ’em! eight!—exclamation points on one page, so you know it must have been a sensational product. With this fabulous appliance’s automatic ice maker, there’s “no filling, no slopping, no mess.”

But what to feed a hungry man on a hot summer night when you don’t have time to whip up a big batch of sloppy joes with Shilling’s or Lawry’s sloppy joe mix? Meat-laden salads! When housewives of the sixties grew tired of the same old coleslaw, Best Foods Mayonnaise had the answer: hollow out a cabbage, scallop the edges of the emptied cabbage head (with kitchen shears, apparently) and pack it to the brim with coleslaw into which you’ve mixed canned tuna. Or maybe you’d prefer to dollop cottage cheese, celery seeds, shredded carrots and green peppers into your coleslaw? Cottage cheese was plopped on everything in the sixties and seventies, as I remember. The iconic healthy breakfast depicted on TV shows or in ads always included a half-grapefruit with a mound of cottage cheese astride the fruit flesh and a maraschino cherry popped gaily on top. Why anyone would want to consume those three items at the same time was always a mystery to me. What if you’re not into tuna slaw or cottage cheese and cabbage? California coleslaw includes crushed pineapple and quartered marshmallows. To wow the guests at your next picnic, serve this candy-sweet coleslaw in a cabbage cut to look like an Easter basket, complete with orange peel “bow,” as shown in the ad, and you’ll “perk up wilted appetites.”

Of course, not every woman alive in the 1960s was a housewife. Many, like my single mother, worked, whether out of pleasure, necessity or both. But the jury was still out on whether those who didn’t strictly need to work to pay the basic bills had either reason or right to do so. Paying women less than men for equivalent work because it was assumed that their work wasn’t essential to their family’s income was common; refusing to promote them or extend them personal credit that wasn’t cosigned by a husband or other man was also an everyday thing. When my mom bought her own house with her own savings in 1970, it was quite an accomplishment and unusual among the people we knew.

This issue of McCall’s has a letter related to an article about working women published in a prior issue. A reader writes of having worked steadily her whole life out of necessity, but angrily derides the choices of women who work out of a desire to serve, for career fulfillment or for personal satisfaction. “I have nothing but contempt for the wives of prosperous men who, in their own boredom and greed, take jobs away from those who really need to work.” She can’t see the validity of working for personal satisfaction or from a desire to help others or to extend one’s world beyond one’s husband’s sphere. These opposing arguments played out regularly in the court of public opinion (and in courts of law) throughout the next couple of decades as women fought to be allowed the same access to education, employment and advancement without respect to whether they had as much “need” to work as men.

When the woman of 1966 worked too hard and felt depressed over her inability to get ahead on the job, whether at home or out in the world of paid employment, what could she do to find the vim and vigor she needed to get through the day when her get-up-and-go and gotten up and gone? McCall’s had the answer for that, too. Anacin, then a popular over-the-counter headache medicine (and still available at drugstores today), was touted as not just a pain reliever but a mood elevator in an ad with the headine “Casts away gloom, depression . . . as it relieves headache pain fast! Anacin has a combined new action that actually casts away gloom and depression as headache pain goes away in minutes. . . . [F]ortified with a special ‘mood-lifter’ or energizer that brightens your spirits, restores new enthusiasm and drive. With Anacin you experience remarkable all-over relief.” Wow! How did this remarkable wonder drug effect such miraculous changes? What super-effective secret ingredients were at work? Anacin’s remarkable active ingredients amounted to nothing more than aspirin and caffeine. Yes, taking two cheap aspirin and a few cups of coffee would “cast away gloom” and relieve headaches just as quickly. After all these years, now you know.