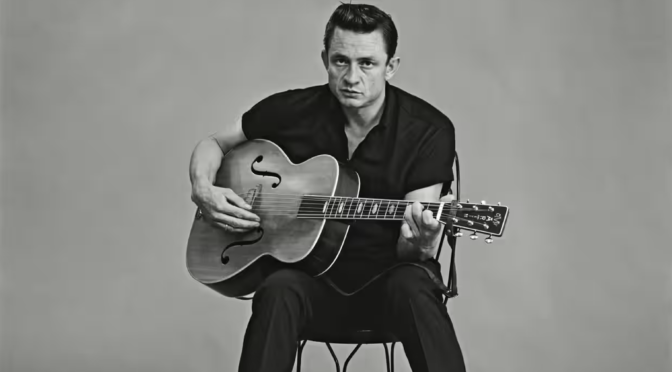

Johnny Cash’s music can be gentle and touching, bold and danceable, fun, silly, even raucous. Sometimes Johnny’s songs are a little hokey, but other times they’re deeply moving. The richness of young Johnny’s voice is a joy to listen to in big hits like “I Walk the Line” and “Ring of Fire.” The quavering of old Johnny’s voice in his exquisite cover of Trent Reznor’s song “Hurt” is heartbreakingly beautiful. But beyond the sheer delight of hearing the man sing in his trademark rich bass voice is the pleasure of learning how Johnny fought and conquered his demons, gave comfort to the afflicted, and stood up and spoke out for oppressed people, over and over again.

Johnny was a badass, a true OG. But it wasn’t just empty posturing. Here are three examples of ways in which Johnny used his huge popularity and influence to speak out for and lift up others through song.

The Man in Black

Johnny wore nothing but black clothes onstage, and in his song “Man in Black,” he sang about what it meant to him:

I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down

Livin’ in the hopeless, hungry side of town

I wear it for the prisoner who is long paid for his crime

But is there because he’s a victim of the times

I wear the black for those who’ve never read

Or listened to the words that Jesus said

About the road to happiness through love and charity

Why, you’d think He’s talking straight to you and me

Well, we’re doin’ mighty fine, I do suppose

In our streak of lightnin’ cars and fancy clothes

But just so we’re reminded of the ones who are held back

Up front there ought to be a man in black

I wear it for the sick and lonely old

For the reckless ones whose bad trip left them cold

I wear the black in mournin’ for the lives that could have been

Each week we lose a hundred fine young men

And I wear it for the thousands who have died

Believin’ that the Lord was on their side

I wear it for another hundred-thousand who have died

Believin’ that we all were on their side.

He went inside Folsom Prison to bring joy to imprisoned men, and sang to them about the pain of being incarcerated. Johnny was never imprisoned himself, but he was arrested seven times on charges such as intoxication, drug use, and actions taken while under the influence. He knew what it was like to fight addiction, mess up in public, and humble himself in order to get himself straight.

Folsom Prison Blues

In the song “Folsom Prison Blues,” Johnny sang about life behind bars, and the pain of it:

I hear the train a-comin’, it’s rolling ‘round the bend,

And I ain’t seen the sunshine since I don’t know when

I’m stuck in Folsom Prison, and time keeps draggin’ on

But that train keeps a-rollin’ on down to San Antone

When I was just a baby my mama told me, “Son,

Always be a good boy, don’t ever play with guns.”

But I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die

When I hear that whistle blowin’, I hang my head and cry.

The Ballad of Ira Hayes

In 1964, Johnny recorded Bitter Tears, an indigenous rights concept album. On it he sang of the oppression and suffering that Native Americans had experienced at the hands of primarily European immigrants to North America over the course of centuries. On it he sang the “Ballad of Ira Hayes” about a Pima Indian soldier who went off to World War II and was immortalized in the photo of the raising of the U.S. flag at the Battle of Iwo Jima. Hayes came home to a nation that reviled him for being Native American instead of honoring him for his service to a nation that had treated his people brutally. Eventually, his difficult life back home in the U.S. led Ira to alcoholism, which in turn led to his early death at the age of 32. Here are excerpts from the ballad, written by Peter La Farge:

Gather ’round me people

There’s a story I would tell

‘Bout a brave young Indian

You should remember well

From the land of the Pima Indian

A proud and noble band

Who farmed the Phoenix Valley

In Arizona land

Down the ditches a thousand years

The waters grew Ira’s peoples’ crops

‘Til the white man stole their water rights

And the sparkling water stopped

Now, Ira’s folks were hungry

And their land grew crops of weeds

When war came, Ira volunteered

And forgot the white man’s greed

Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won’t answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinking Indian

Or the marine that went to war

There they battled up Iwo Jima hill

Two hundred and fifty men

But only twenty-seven lived

To walk back down again

And when the fight was over

And Old Glory raised

Among the men who held it high

Was the Indian, Ira Hayes

Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won’t answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinking Indian

Or the marine that went to war

The song became a popular anti-war, pro-Indian protest song while the Vietnam War was raging, despite the fact that many radio stations refused to play it. Although Johnny, who joined the Air Force during the Korean War, and his wife June Carter Cash played for the troops in Vietnam and respected their service deeply, he had antipathy toward the Vietnam War. He sometimes expressed this, to the consternation of his more conservative fans. They found Cash’s progressive politics and support of civil rights and equality for all distasteful. Some turned away from Johnny as a result, but he refused to court bigots. He believed that following his conscience was more important than making more money.