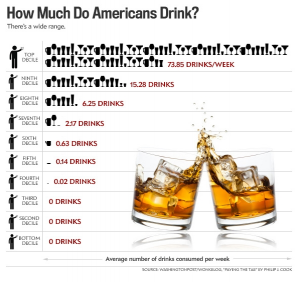

Image source: Washington Post/Wonkblog, “Paying the Tab” by Philip J. Cook

A new study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) attributes 9.8% of all U.S. deaths among adults aged 20 to 64 to excessive drinking, and alcohol is involved in 5% of all U.S. deaths of people under the age of 21. the U.S. alcohol-consumption average is 556 drinks per year (under 11 drinks per week, or 1-1/2 drinks per day), those figures are misleading. Almost 30% of the U.S. population never touches alcohol, and another 30% only drinks on special occasions—once every two weeks at most. That means the other 40% of the population is downing all that liquor.

While the number of alcohol-attributable deaths (AADs) in the U.S. is lower than rates across most of Europe and in much of Central and South America, it is significantly higher than the rate of AADs reported by the United Kingdom and Ireland, despite the high incidence of binge drinking in the UK. This is likely to reflect a difference in the definitions of “alcohol-related” deaths among nations. While rates of binge-drinking vary widely across the U.S., the overall prevalence of binge-drinking among U.S. adults in 2011 was 18.4%. Britain’s National Health Service estimates that over 50% of Britons binge-drink regularly, though official estimates are in the 28% range. In Ireland binge-drinking is a weekly event for 21.1% of the population, and 39% engage in it at least once a month according to official estimates, but underreporting of alcohol use is standard and expected in self-reported surveys. One would expect the number of AADs in these countries to similar to or greater than those in the U.S., but their definitions may vary from that of the CDC, which says, “These deaths were due to health effects from drinking too much over time, such as breast cancer, liver disease, and heart disease, and health effects from consuming a large amount of alcohol in a short period of time, such as violence, alcohol poisoning, and motor vehicle crashes.”

While many people have a genetic predisposition to become alcoholics, the amount of liquor people consume is strongly influenced by social situations and peer behavior: people tend to see their friends’ behavior as the norm and assume that consuming anything less than their most inebriated friends makes them moderate drinkers. According to the CDC, heavy drinking constitutes 8 or more drinks per week for women (just over one drink per day) and 15 or more drinks per week for men (just over two drinks per day). Binge drinking corresponds to four or more drinks on a single occasion for women (which is equal to just under one bottle of wine) or five or more drinks on a single occasion for men (just under a six-pack of beer). Even moderate drinking (one drink per day for women, two for men) significantly increases risk of breast cancer as well as liver, colon and esophageal cancers and cancers of the mouth and throat. Moderate alcohol use also aggravates mental health disorders (including depression) and increases injury risk. About 70% of drinking-related deaths involved men.

Researchers note that the data on alcohol consumption used to calculate alcohol-attributable deaths were based on self-reporting, which means it’s quite likely that U.S. alcohol consumers underestimated their consumption. Britain’s National Health Service says that people around the world tend to underestimate their drinking by about 40-60%. Also missing from the estimates were data on the deaths of former drinkers. Since former drinkers may have stopped drinking because of alcohol-related health issues that ultimately cause their deaths, it is likely that their absence from the study artificially lowers the number of deaths caused by alcohol, which brings the number of U.S. deaths alcohol-related deaths to well above one out of ten adults and one out of twenty minors.