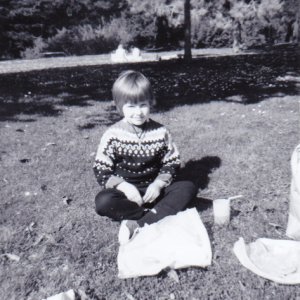

The author in Golden Gate Park in the late 1960s

Among my childhood photo albums are pictures of me wearing daisy chains and sitting on the grass in Golden Gate Park. I have vivid memories of spending time with my father and his friends in the park and in the adjoining Haight-Ashbury district when I was a very little girl. I was tiny, but I remember San Francisco, the epicenter of the hippie movement, during 1967’s legendary Summer of Love and in the years thereafter.

Though I grew up in the suburbs, I often visited what people in the Bay Area refer to simply as The City. All my life I have felt a special pride in my connection to San Francisco. My mom gave birth to me there, in a hospital just a few blocks’ walk from the famous intersection of Haight and Ashbury Streets. My dad (whom I only lived with for the first few months of my life, and only saw occasionally from babyhood onward) brought me to various hippie happenings there during his visits with me from the time I was about three years old. He hoped to make up for what he saw as the soulless bourgeois childhood I was supposedly experiencing in the Bay Area’s eastern suburbs.

The PBS American Experience documentary on the Summer of Love shows a San Francisco very much as I remember it during that time, albeit from about three feet off the ground. As a young child, I found San Francisco’s hippies often scary and off-putting. Even as a very little girl I had a sense of the importance of personal space and a desire that things be done safely, with purpose and according to plan. I was much more of a cautious goody-goody than even my mother, a high school teacher whom my father denigrated for being too suburban. I followed rules; my father and his friends generally did not. My dad hated authority, rules and The Man, so he and his friends would take joy in challenging the establishment whether or not I was with them.

I was always the only child present on visits with my father, and was usually ignored, so I spent a lot of time in watchful anxiousness, hoping not to be put in harm’s way. I was frightened by his and his hippie friends’ lack of concern with their actions or with me; they were lackadaisical, careless, loudly vulgar and sometimes stoned, so I felt ill at ease and unprotected with them.

People often talk about how loving and peaceful hippies were, but I saw also an enormous amount of anger directed by them toward rules, history and authority. That anti-establishment anger was often channeled for good in such campaigns as the fight for full and equal rights for African-Americans, women, Native Americans and homosexuals, among other downtrodden groups. The often strident and unpleasant but necessary challenges to the entrenched establishment gave young people in particular the courage to question the wisdom of their leaders and force their government to justify its wars. They gave the populace the courage to stand against unjust laws and corrupt political practices. It was this movement that eventually gave journalists the courage and necessary establishment backing to bring down a powerful sitting president during the Watergate scandal just a few years later.

While the nation often benefited from the outspoken challenges of those who had felt stifled by government, big business and the limiting social mores left over from the 1950s, there was also an upsurge in more generalized antisocial behavior. The rise of the hippies led not only to social activism, peace and love, but also to huge numbers of (mostly) young people breaking rules just for the hell of it. Many wrapped their destructive or selfish behavior in a cloak of righteousness. Some took advantage of the new social openness to examine their psyches and motivations honestly and to try to relate to others in more direct and healthy ways; others just found this newly socially acceptable preoccupation with self an excuse for narcissistic behavior.

The ensuing decade of the 1970s was dubbed “The Me Decade” with reason. During the 1960s, modesty had lost favor while self-regard and constant awareness of one’s own needs and desires became viewed as positive things. Exuberant self-expression and in-your-face sexuality went from being shocking in the early 1960s to being surprisingly common within a decade. In the early 1970s, when I visited the high school where my mother taught (and which I would later attend), obvious bralessness was very common not only among the students but even among teachers. Some of the younger teachers wore hot pants to school. Overt sexuality was, however, considerably less evident in high school teachers’ fashions by the time I myself entered high school later in the seventies.

To be fair to those who were part of the laissez-faire San Francisco hippie culture of the 1960s, I saw plenty of self-absorption and self-aggrandizement even among more establishmentarian suburbanites during that time and in the decade that followed. Social boundaries were not well respected in general in the late 1960s; millions of people (not just hippies) were sharing their formerly private thoughts (not to mention their bodies and lots of adult-themed talk and media) with great abandon and carelessness, and we kids were often exposed to too much knowledge too soon. Those of us who appreciated having some boundaries in our lives were often ignored or denigrated by people who felt superior because of their mod, carefree sensibilities. Some, like my father, mistook the desires of others (like his young daughter) to follow laws, keep order or avoid conflict or offense as being necessarily conservative traits. They are not.

There was a middle ground in which people challenged the status quo more gently; they didn’t want social anarchy but still believed strongly in the promise of liberalism. Yes, many San Franciscans, hippies included, sought peaceful, meaningful, respectful social change and worked hard for it. But from my own perspective, as a very young person, I saw measured, realistic and inclusive social activism in the suburbs, too, even among those whom my dad and his friends found so hopelessly square.