[Revised from version originally published in April 2015.]

Load up on guns, bring your friends

It’s fun to lose and to pretend

She’s over bored and self assured

Oh no, I know a dirty word

Long before Kurt Cobain displayed the depth of his hopelessness to the world by taking his own life, his fans had known he was suffering. Anyone who has listened to Kurt Cobain sing “Smells Like Teen Spirit” has heard the pain in his voice. Every Nirvana song is built upon a platform of angst—the music, the lyrics, the growls and wails all make the turmoil and drama inside Cobain’s head quite clear and accessible for anyone to hear. This transparency of feeling is what makes Nirvana’s music great and greatly beloved: it taps into a primordial well of anxiety, anger, longing and disillusionment in listeners and makes us feel as if our own personal, raw feelings are being scooped up, wallowed in and worn like warpaint by a rock god for all the world to see.

The obviousness of Cobain’s extreme pain was so evident to millions of people years before his suicide in 1994, so it comes as a shock to watch interviews with his friends and family and see how many cries for help they ignored, how little aid they sought for him, how limited were their resources in guiding him toward hope even after he became one of the most famous people in the world. The very elements of his psyche that made his art so powerful and meaningful to others were the parts that caused him the most misery. His charisma, stubbornness, insularity and difficult personality seem to have paralyzed those who should have seen him clearly and helped him most directly. These same characteristics and his remarkable ability to build a bridge between himself and other disaffected souls brought him a level of scrutiny that made him feel trapped in a dangerous tidal wave of success that he was constantly trying to ignore and retreat from. It’s as if he was hiding in plain sight.

With the lights out, it’s less dangerous

Here we are now, entertain us

I feel stupid and contagious

Here we are now, entertain us

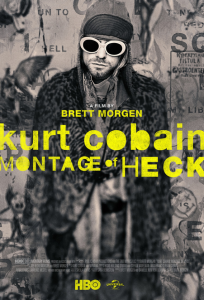

All of this becomes devastatingly clear in Brett Morgen’s excellent HBO documentary Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck. The first film about Cobain to have the support of his daughter Frances Bean Cobain (who is also one of the film’s executive producers) and her mother, Kurt’s widow Courtney Love, this documentary could never have been made without their treasure trove of audio recordings, videos, home movies, drawings and family photos and access to Cobain’s diaries and notebooks. All of these elements come to life in stunning animated montages that make us feel as if we’re in the room with Kurt, his mom, his wife, his baby and bandmates Krist Novoselic and Dave Grohl. Sometimes we feel as if we’re inside Kurt’s head as well.

Come as you are, as you were

As I want you to be

As a friend, as a friend

As an old enemy

His violent and disturbing drawings, his remembrances of distressing moments in his personal history and the pained, sad stories of those with whom he lived and worked make abundantly clear how lonely, frightened and angry he was from a very early age. But the home movies of him as a baby and child show a heartbreakingly sweet and pretty little boy with a beautiful voice. He was hungry for attention and constantly in need of deep soothing that he rarely received. It hurts to see him so fresh and so loved, and to know that his overwhelmed parents, stepmother, siblings and friends had no idea how to deal with his enormous kinetic energy, his destructive impulses or his lack of self-control. The things he needed most—stability, understanding, unconditional love and safe ways to soothe himself—seemed nearly always out of reach, so he went for one dangerous activity, addiction or relationship after another, and that resulted in self-loathing and mental disintegration.

Two interviews really stand out among those in the film. One was with his stepmother, with whom he had a very difficult relationship. She recognized how abandoned and unwanted he must have felt when he was kicked out of his parents’ houses and moved from one to the other, then went off to a grandparent and moved back around through the family again. She expressed regret that she hadn’t recognized his pain at the time but could only be frustrated by his acting out and worried about the effect of his behavior on his siblings. Bandmate Krist Novocelic, long his close friend, expressed great sadness that he was unaware of how serious Kurt’s problems were during his life even though he saw evidence of Kurt’s rage and watched him self-destruct. He says in hindsight it is obvious that Kurt was in extreme pain and that there were numerous red flags and cries for help, but he wasn’t able to recognize their seriousness at the time.

Novocelic also noted something crucial to an understanding of Kurt’s enormous antipathy toward fame and success: he said Kurt had a huge fear of being humiliated. As we watch Kurt in films and videos and hear his words, it becomes clear that he hid his fears with bravado, dark humor, dramatic performances, drugs and acting out. He derided establishment values and behaviors and deliberately set up barriers between himself and those who might have been best able to recognize and help him. And of course, it is that raw, urgent ugliness inside of him that sometimes comes out in gruesome drawings, in his bashing his guitar to smithereens on the battered wood floor of his own house, or in refusing to bathe or wash his hair for days, or living in squalor and backing out of major tours so he could go home to do little but play guitar, have sex and shoot up for days or weeks on end.

It is that very grunginess in his personal life that bled, sometimes almost literally, into his music, and made it so accessible, thrilling and fresh to a youthful audience tired of the smooth, highly produced technopop of the 1980s. Cobain’s squalor and literal stink combined with a vulnerability, a gritty poetic streak and a compulsion to create helped him build a dirtily sexy persona, but they also pushed him into a dangerously intense public world that made him endlessly terrified of being exposed, embarrassed, ridiculed, overadored and ultimately used up. So he used himself up in a hurry before life had a chance to do it to him.

I found it hard, it’s hard to find

Oh well, whatever, never mind

The urge to create and the urge to destroy, including the urge to self-destruct, were always living side by side within Kurt Cobain, and his overwhelmed family members shunted him back and forth among houses a number of times during his childhood, recognizing his neediness but experiencing it always as a destabilizing and dangerous force that they couldn’t control and couldn’t stand. He also had a long history of serious and excruciating abdominal pains that caused extreme and frequent pain and sometimes bloody vomiting, but there was little money available until the end of his life for psychological help or appropriate medical care. So he developed dangerous ways of self-medicating with food, drink and drugs that exacerbated his ill health. By the time he had the money for proper mental health support and medical care, his dangerous habits were well ingrained, and his beloved companion and wife Courtney Love was herself so drug-addled, angry and self-destructive that she could only feed into his addictions and his rejection of others’ attempts to offer help. When her eye started to wander and he recognized that even she, the partner whom he thought understood and loved him better than anyone, was on the verge of betraying him, he lost all hope, attempted suicide, and then successfully finished the job with a gun a few days later.

Hey, wait, I’ve got a new complaint

Forever in debt to your priceless advice

Why would someone want to sit through two hours of this dark story with so many regretful loved ones sitting stricken in front of the interviewer and recounting their memories with wringing hands and guilty eyes? Because the pain of his story, like the pain in his music, is compelling even as the details are sometimes repellent. Some of his memories, words and images are grim and disturbing, but watching the intimate dynamic between him and Courtney, drug-addled and gritty as it often was, shows why they were drawn to each other—admiration, understanding and humor are all evident, as is a certain pleasure in courting death and mayhem. It hurts to watch him hold his baby Frances with such loving tenderness and read and hear his words of devotion, then later see him barely able to hold her on his lap, so drugged-out and nearly incoherent is he in one awful scene. It is hard to watch knowing that Courtney, a friend filming the scene and another helping with the baby were all present, and, like everyone else in the film, they observed the clear self-destruction of the man but no one either would or perhaps could do anything to pull him back from the brink.

I saw the film in Seattle’s Egyptian Theater, which is right in the neighborhood where Cobain had his last meal. One block from the theater is Linda’s Tavern, where he was last seen alive on the night before he shot himself through the head. The film is currently in a few theaters around the U.S. and in the U.K., and is garnering high praise for its intimate portrayal of the man and his life and his ardent, nearly compulsive need to create. I’m glad to have enjoyed it in a cinema where the never-before-seen concert footage was especially powerful and immersive and the intimate moments felt even more immediate. I’m even gladder that it will be available to so many more via HBO television showings.

I’m so ugly, but that’s okay, cause so are you

We’ve broken our mirrors

Sunday morning is everyday for all I care

And I’m not scared

While the film has received mostly very good reviews, some have complained that it is uneven and a bit jumbled because of the lack of a narrator and the sometimes abrupt switches between interviews with those who knew him, private film footage, concert footage, images of his writing and art and montages of animation and recordings. Boyd van Hoeij of The Hollywood Reporter wrote that the film is “impressive in parts, but wildly uneven as a whole.” I found this unevenness and the montage style particularly appropriate for the story of a hyperkinetic, often drugged-out man with serious mental and emotional problems. I might have found the style more annoyingly disjointed had it been used to tell the story of a different subject, but in this case the style illustrates how overwhelming it must have felt to live inside of Cobain’s brain and body. The barrage of images and sounds approximate the cacophany of a grunge concert, a life of rock and roll excess and the disabling and endless waves of chronic and extreme physical and emotional pain he felt. All of that is shown amid reminders of how much love and admiration those around him felt and wanted to share with him alongside the frustration and confusion they felt over his extreme emotions and behaviors.

A denial, a denial, a denial, a denial.

The film, which gets its name from a musical collage made by Cobain with a four-track cassette recorder before Nirvana became famous, is no feel-good movie. It is often funny, sometimes darkly beautiful and occasionally mesmerizing, but it is also a very raw view of the life of a dangerously mentally ill and emotionally damaged human being. Even though it shows how difficult and ugly he and his life could be, it also helps us see his vulnerability, humanity and his hunger to create, and it makes clear his devotion to his wife and child.

This film helps to humanize Kurt Cobain without lionizing him. Seeing how far back his deep emotional illnesses went also helps us to empathize with him and feel sympathy along with the disgust his actions sometimes inspire. The film shows how off-puttingly, determinedly filthy, squalid and unhealthy his lifestyle often was (though he and Courtney did sometimes live in luxury hotels in Seattle and elsewhere once they became wealthy), and interviews with his mother and his widow give some glimpse into their own sometimes impaired ability to see how much of a part each of them played in his feeling unsupported and betrayed.

He’s the one

Who likes all the pretty songs

And he likes to sing along

And he likes to shoot his gun

David Fear of Rolling Stone described the film as “the unfiltered Kurt experience,” noting that Cobain is shown “not [as] a spokesman for a generation,” but as “a human being, and a husband, and a father.” Frances Bean Cobain said at the documentary’s premiere in Los Angeles, “After seeing it, I thought I could only watch it once. But the film that [Morgen] made—I didn’t know Kurt, but he would be exceptionally proud of it. It touches some dark subjects, but it provides a basic understanding of who he was as a human, and that’s been lost.”

I agree.