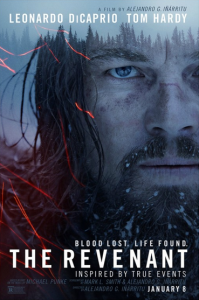

At the core of this grim film about pain, loss and revenge, The Revenant is a story about steel-cored adventurers whose every day is full of extreme but self-imposed hardships. This film, a fictionalized account of the story of actual 19th century fur trapper Hugh Glass, shows better than any other the brutal conditions under which fur trappers lived on North America’s frontier. Nature is a living, breathing, bloody-clawed character in this film, as much a part of the cast as Leonardo DiCaprio or Tom Hardy. Emmanuel Lubezki’s cinematography is stunning: he captures both nature’s grandeur and man’s brutality in this film.

Stories in which characters face extreme adversity allow actors to emote more dramatically, showing not only their acting ability but also their willingness to suffer for their art. When an epic is directed, shot, acted and edited this masterfully, the arc of the story, the flow of action, the building of character and the depth of each loss all reverberate more intensely within the viewer’s heart.

The Revenant overflows with evident extremes: constant cold (which left the actors courting hypothermia and frostbite more than once); bloody brutality; heaving, spitting, screaming vengeance; terrifying physical danger; a highly protective mother bear; hand-to-hand combat between invading white trackers and indigenous Native Americans; horses undergoing the worst possible disasters; even creatures seeking respite in the dead bodies of other creatures. It is to the great credit of the cast, and DiCaprio and Hardy in particular, that these characters feel not like strutting caricatures of good and evil but like actual human beings.

The scenes involving closeups that show flickers of the subtlest emotions are as thrilling as those involving CGI bears, horses or eviscerations. Hardy is almost unrecognizable, not only because of the facial hair and prosthetic scalped pate but also because of his quirky accent with its unexpected twangs and turns. His character is thoroughly unlikable, but also so uneasy that we can never trust ourselves to know him or anticipate his next move. Despicable as his actions may be, his motivations are clear, yet he leaves us perpetually off our guard. This keeps this long, intense movie from sinking under the weight of his character’s badness. In a year that also saw him give laudable performances in Mad Max: Fury Road and in Legend, the brutal but entertaining story of London’s deranged mobsters Ronnie and Reggie Kray, Hardy’s stunning portrayal of brooding, bloody John Fitzgerald in The Revenant is a career highlight.

After giving so many fine performances in his long career, Leonardo DiCaprio truly earned his Oscar for The Revenant. I was first moved by him when he was a talented teen giving stunning performances in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? and This Boy’s Life. With the exception of Titanic, which I thought elicited some of his and Kate Winslet’s worst performances, I’ve watched his career unfold with great pleasure. His role in The Revenant has all the Oscar-friendly elements—the physical hardship, extremes of pain, fear, loss and vengeance—but it also requires that we utterly believe in the living, breathing reality of his character’s plight, and that we want to stay with him through each new horror despite our own great discomfort.

If the story were just about a wronged man seeking vengeance, we might grow tired of the chase or grow to hate the man who seeks revenge, but this long saga, which focuses heavily on DiCaprio during long solitary scenes, lets us feel and sympathize with the reasons behind his vengeance. We sense his great pain, his loss and his essential decency because Leo insists that we do. DiCaprio’s character must impress us with his fortitude and his ability to surmount the nearly insurmountable, time and time again, but in order to care about him we must be constantly reminded of his vulnerability, and no actor today is better able to display alternating vulnerability and quick-on-his-feet mental resourcefulness than Leonardo DiCaprio.

Director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s treatment of the story incorporates scenes of silent, lyrical natural beauty in the sweeping manner of director Terrence Malick. The two share the ability to step back from an engrossing, intense situation and remind us of the environment in which it takes place, allowing the audience to breathe. They let us rebalance ourselves to better evaluate the mental states of the characters to whom we feel so closely drawn. These directors share a penchant for magical realism and sensual naturalism, something that was evident in Iñárritu’s award-winning direction of the fantastical (and Oscar-winning) film The Birdman. That film was alternately claustrophobic and expansive, with the most explosive and off-putting scenes taking place within the confines of a theater, and the true expression of the main character taking place during bursts of real or imagined flight. In The Birdman, Iñárritu allows us to believe that a man can feel trapped and caged while alone in a barren landscape or free to fly while sitting cross-legged in a tiny theater dressing room, his mind miles away from his levitating body.

The Birdman threatened always to drift away into the realms of the irrational while simultaneously forcing the audience and the characters to face life’s real limitations and gravitational pull. The Revenant explores what it’s like to be bound to earth by pain, determination and oppressive nature while being urged forward by elements of the indomitable human spirit that are eternal, ineffable and stronger than gravity: one human being’s love for another, and a determination that even death might be conquered in order to honor and hold onto the spirits of those whom we have loved and lost.