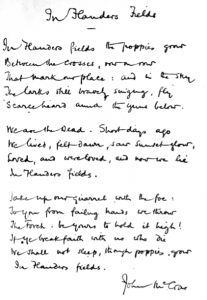

J. K. Simmons (left) and Miles Teller in Damien Chazelle’s film Whiplash

On rare and special occasions, I will walk out of a movie theater quivering with excitement about something I’ve just seen, my heart racing and my synapses tingling as my hands fumble for my cell phone, so anxious am I to call someone right away to rave about a cinematic work of art. I’ve often seen performances that moved me and thrilled me, but when a whole film is crafted with power, tension, exceptional acting and directing, a fine script, masterful editing and a thrilling story arc, I walk away transported and inspired. I felt that way after seeing modern classics like The Usual Suspects, American Beauty and Brokeback Mountain, and this week I felt that kind of thrill after seeing the new indie film Whiplash, which stars Miles Teller as a promising young jazz drummer and J. K. Simmons as his sadistic mentor and tormentor.

Whiplash was originally mounted as an 18-minute short film written and directed by 29-year-old Damien Chazelle, which he presented to great acclaim at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival in hopes of attracting enough funding to make it into a full-length film. The gambit worked, and the full feature film was created with a tiny $3.3 million budget and went on to win 2014 Sundance Film Festival’s top audience and grand jury awards. I must warn you, it starts out at a heart-palpitation-inducing level of energy and anxiety and only builds from there. My pulse was still pounding 20 minutes after the film ended—watching it is a bit like having a 107-minute anxiety attack, so don’t expect a light evening at the movies. The film editing by Tom Cross was outstanding—there was power, energy and intensity in every moment thanks to the way Cross and director Chazelle framed and cut each scene. The cinematography by Sharone Meir was also evocative, sometimes claustrophobically close, and together Cross, Meir and Chazelle built the energy levels during the practice and performance scenes to almost painful heights.

Chazelle was himself a jazz drummer in high school, where he had an intense music teacher who was the inspiration for the character of the hectoring, threatening music conservatory jazz band leader played with astonishing power by J. K. Simmons in Whiplash. Miles Teller, who impressed critics with his performances in The Spectacular Now and Divergent, was himself a talented, self-taught rock drummer in high school, but to play the driven, obsessive, arrogant young jazz drummer in Whiplash, the normally lighthearted, enthusiastic Teller had to learn the very different jazz drumming style. He became proficient enough to make audiences believe that his character Andrew Neyman might just be a prodigious, one-of-a-kind talent, a Buddy Rich for the new millennium. His drumming scenes are riveting, and as we watch him wince, writhe, sweat and even bleed all over his drums, we know we are watching a dangerous but exciting metamorphosis. That really is Teller playing, too, though performances were teased out of multiple takes and edited seamlessly by editor Tom Cross. For several years Hollywood insiders have touted Teller as one of the young actors to watch, and he will soon be part of a major franchise as he’s been given the role of Mr. Fantastic in the new Fantastic Four reboot. He’s a fine actor, and in Whiplash he also gave the most thrilling drum solo performance I’ve ever seen on film.

This film spoke to me with particular power because I myself had an intense, bullying, sometimes violent mentor as my first choir director when I was a child. I attended an elementary school famous for its excellent choir, and couldn’t wait till I got to fourth grade so I could audition. I had been steeped in music my whole short life, attending my mother’s voice lessons with her, listening to her sing and play piano while I took my baths each night, borrowing records from the library to enjoy with her, sitting in the orchestra pit with my mom while she accompanied local musical productions on the piano and turning the pages when she played and sang at weddings. My mother’s friend Owen Goldsmith was not only a choir director but also a composer and arranger, and Mom was the first person to play and sing many of his compositions, so I would sit on the floor of his home drawing or enjoying his books of Addams Family cartoons while the two of them made music late into the night. I sang at the piano with my mother most evenings from the time I was two till I went to college, and during all my visits home until she died years later. When we got together she sang harmony, I sang the melody, and we sang everything from show tunes to European art songs, folk songs to pop songs, hymns to novelty hits. When I was 13 she married a violinist and conductor, and yet more music and musicians came into our lives, including a wonderful evening spent with singer Marni Nixon in our home the night before she sang with my stepfather’s orchestra.

When I auditioned for the choir, the tall, trim, imposingly grim-faced Mr. Kerr had me sing a few intervals and melodies while he sat at the piano. He showed no emotion but, despite his taciturnity, he was pleased with me. I was invited to join both the primary and the honor choirs. Within minutes of my arrival at the first rehearsal, it was clear that I was in for more than I had bargained for.

Mr. Kerr ran the choirs in his spare time; it was an unpaid position but one he cherished. He was primarily a fifth grade teacher famous for his friend Roscoe, a wooden paddle which he was happy to use on the bottoms of children who displeased him. He made a show of adding notches to Roscoe each time he hit a child with it. By the 1970s, he had to secure the permission of parents before he could smack their kids, but several of the “difficult” kids in my class (including a deaf boy with ADHD) were regularly smacked while I was in his fifth-grade class.

Mr. Kerr was no less harsh in his responses to any failure by choir members to follow his strict and unwavering laws. If a child showed up late to a rehearsal for any reason, he was not allowed in. The doors were locked and he could not enter. If someone missed more than two rehearsals, she was dismissed from the choir, end of story. When people talked back, they were yanked out of place by a red-faced, bug-eyed, looming Mr. Kerr, dressed down completely and were booted out of the choir.

Discipline was harsh and consistent and we lived in constant fear of his displeasure. But he was an exceptional musical director whose singing and performance instruction still informs my performances today. There was no excuse for being sharp or flat, for missing an entrance or ending a phrase sloppily. Every eye was on him at every moment. We all stopped at exactly the right moment, held our carefully shaped vowels and only cut them off with consonants at the very last second. Breath was properly supported and there was no whining nasality, there was no swooping up to notes, and there were no “blatty” broad vowels. Phrases were meant to be held no matter how hard it was to keep them going; there were no haphazard ragged breaths. If breaths needed to be staggered, he would tell us exactly how to stagger them through each section so there were never too many people breathing at the same time, and he knew when anyone, anywhere had made an error. Any child taking a breath in the middle of a word risked sudden death.

There were no fidgety hands or wandering eyes, no looking out at the audience, no breaking focus or slacking off on energy until the end of the song when he signaled to us that we could at last stand at ease. Every child wore a spotless uniform of cornflower blue skirts and white blouses for the girls and matching light blue blazers and black slacks for the boys. Each right hand grasped the matching left thumb and our hands were held in front of us in this folded position whenever we were on the risers. Knees were slightly bent so that we didn’t lock them and faint for lack of enough oxygen flowing throughout our bodies and to our brains—usually. When someone fainted during a performance, the show went on.

We sang intricate scat-phrased versions of Bach bourrées, learned many Latin hymns and movements from various major composers’ Masses, a score of spirituals, folk and holiday songs, and the occasional pop song. Each song was explained to us carefully; we had to think about what we were singing and why, what each inflection meant, what each phrase called for in order to get the point across. When we sang “Sinner, please don’t let this harvest pass” our plaintive cry nearly made us weep; sometimes we even made Mr. Kerr cry. When we sang in Latin or Hebrew, he made sure we knew what every word meant. When we sang folk songs or spirituals, Mr. Kerr put them in context and explained what place they had in the lives of those who had written and sung them. And yes, most of the songs we sang in this public school choir had religious overtones, but that was never questioned in the 1970s.

We were the top children’s choir in our division and we won gold medals and blue ribbons. We sang on the radio and on local television. I was the only soloist during the three years I was in the choir, and sat with my family on Christmas morning as we listened to me sing over my aunt’s stereo speakers. It was exciting and shocking to hear myself on the air, but Mr. Kerr wasn’t about to let it go to my head.

He was determined not to let any favoritism show; I may have been given a solo and permission to join the choir early, but I was not to be given any praise or encouragement beyond that. When out of fear I once responded to his telling me that he wanted me to sing another solo with a demurral, he said fine, no more solos ever. He never offered me another. He saw what I thought was a one-time refusal to sing due to nerves as a challenge to him and as an example of my going against his directive: he was my captain and I had refused a direct order, and now I was a bad example for the troops.

I worked so hard for him, but it was never enough. I was deathly afraid of letting down my teachers or my mother, herself a teacher in the same school district, so when I was in his fifth grade class as well as in choir, I made sure my grades were better than anyone else’s. Yet he dismissed my efforts and instead praised my closest academic rival, Ricky, when he spoke to my mother during a parent-teacher conference. He spoke admiringly of what a boy’s boy Ricky was, how he wasn’t a “pantywaist” like other boys. My mother came home disgusted and offered to move me out of his class. I begged her not to; I wanted to be in his choir no matter what, and I’d live through the humiliation and anxiety I felt every day in his class rather than have him look down on me for pulling out from under his iron thumb.

Mr. Kerr was an angry martinet, but he knew how to get the sound he wanted from his choir. He knew how to make us pay attention, how to make us understand what we were doing and why, how to keep our energy up and finally how to lead us to give captivating performances.

I still resent him for reducing children to tears, screaming at us and calling us names, for hitting us and humiliating us. It was wrong and damaging. But when I consider the lessons I learned from him about how to put a song across, how to follow direction, how to support a tone and project it, and how to work with a large group as if we were one entity—he was able to teach these skills like nobody else I have ever seen. Partly we worked as hard as we did out of fear, it’s true, but mostly I believe it was because of the intensity of his focus, his dedication, and his teary-eyed ecstatic face when we performed as he knew we could. I hated his methods and don’t know whether on the whole he did enough good with his amazing choirs to balance out the harm he did to so many fifth graders cringing under his tutelage. But all the kids I knew who studied music under him knew what it was to be real musicians. His methods were disturbing and I think often immoral, but there was no questioning the loyalty or the power of his choirs.

Director Chazelle takes the stereotype of the brutal directorial dictator further than my own choir director ever did, but the questions he makes us ask ourselves will be familiar to anyone whose child is involved in a rigorous, competitive activity. Whiplash requires that we consider whether the delirious joy of creating a masterpiece that pushes an artist beyond his previous limits justifies the monomaniacal arrogance, drive and willingness to risk everything it may take in order for that young person to achieve mastery. What are the acceptable limits to abuse, debasement and ego destruction of another in the service of pushing someone beyond all understood boundaries and into a whole new realm? Can the dehumanizing pain and occasional complete ego destruction that come with breaking someone down in hopes of driving him to new heights ever be justified? How much sacrifice, humiliation and defeat should we allow anyone, let alone a very young person, to experience in order to push the limits of creation or expression or athletic prowess?

Teller is the ostensible star of this film, but the greatest thrill of it comes from the tension between himself and his co-star J. K. Simmons, who is mesmerizing and horrifying as the charismatic band leader Terrence Fletcher. He draws young Andrew in, gives him hope and builds up his ego, and then systematically dehumanizes his young protégé, giving just enough encouragement to mess with the young man’s mind before again dragging him through Hell. This disturbing character’s occasional bursts of warmth and insight and his touches of vulnerability make him one of the great villains of cinema—it’s that touch of humanity in the monster that makes him even more frightening, because then we can catch a glimpse of ourselves in him. Simmons is already on the year’s short list of shoo-ins for an Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination, so fine is this performance and so crucial is it to the arc and power of the story.

But it is Teller who must convince us that he has the audacity, sheer talent and burning ambition to make stardom a possibility. His face is wonderfully expressive as he shows us the gamut of emotion from fear and insecurity to modest pride to rage to shame. Teller was in a life-threatening car crash in 2007 that left him with many noticeable scars on his face and neck, scars that were not covered up for this film, and which give him a raw, real, vulnerable quality that helps to balance the moments of extreme arrogance that his character must burrow into in order to do what he has to do, but which also alienates those with whom he craves connection.

In interviews, J. K. Simmons and Teller come across as bright, warm, incredibly likeable actors, and Simmons says they had a great chemistry on the set that made it easier for them to get through the harrowing scenes in which Simmons was abusing Teller. Teller has a light-heartedness that allowed him to let all the abuse roll off his back, and Simmons is a warm, funny, modest man whose strong features and booming voice belie the affable fellow underneath. He is used to playing supporting roles and is skilled at making his costars look good. He had a long career as a stage actor and singer. Simmons played Benny Southstreet in the 1992 stage revival of Guys and Dolls with Nathan Lane and Peter Gallagher, which I was fortunate enough to see live on Broadway that year. He has a fine singing voice, which he demonstrated during an episode in which he played neo-Nazi Vernon Schillinger in the prison-based television show Oz. Simmons is familiar for roles such as the father in the film Juno and as the spokesman in the Farmers Insurance ads. He’s a regular on the TV series The Closer, he plays newspaperman J. Jonah Jameson in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy, and is the voice of Cave Johnson in the video game Portal 2. He only became a regular screen actor in his 40s after twenty years on the stage, and he credits Sidney Poitier, with whom he acted in one of his first film roles, for being a gracious and generous mentor to him. Seattle area readers will enjoy learning that Simmons’ sister, Elizabeth Simmons-O’Neill, is a writing professor at the University of Washington in Seattle, and is director of the Community Literacy Program.

Whiplash is named for the Hank Levy jazz composition that, along with Duke Ellington’s “Caravan,” is at the musical center of the film. It is indeed a wild ride that threw my head back and made me dizzy. I can’t wait to see it again.