[This article originally appeared on Laura Grey’s Little Hopping Bird blog.]

Is graffiti art? And if it is, is the defacement of others’ property ever justifiable in the service of art? When is graffiti (or “guerilla art,” or “street art”) okay? When it says something meaningful? When it’s well done? When it’s pretty? When famous people say it’s art?

Let’s suggest for a moment that it’s always wrong to deface others’ property. After a graffiti attack, once a property has already been defaced, is there ever a justification in leaving the defacement/art in place? What if it’s really great-looking, astonishingly intricate, brilliant in its message: would those circumstances justify the illegal (and some would say unethical) action that created it?

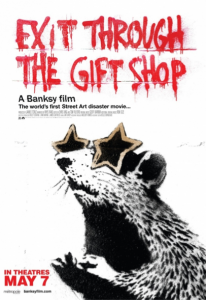

These are important questions to consider when discussing or viewing graffiti art or “street art,” and a documentary that addresses them would be fascinating. However, Exit Through the Gift Shop, the excellent new documentary on street art, doesn’t address any of them. And it doesn’t need to. Subtitled “The world’s first Street Art disaster movie,” it’s a fascinating film on its own merits, even though it leaves the ethics of all the principal characters in the film essentially unexplored. The film itself may be at least in part an elaborate hoax. If it is, it’s still worth seeing.

The most famous graffiti artist in the world, and certainly one of the most talented, is a Briton who goes by the pseudonym Banksy. Banksy is a wily and elusive character who has been creating graffiti art, first in England and then internationally, since the early 1990s. He began as a common tagger but after too many run-ins with the law, he decided he needed to develop a new style that would allow him to prep a public outdoor space, create his art as quickly as possible, then disappear before cops could show up and arrest him. He developed a system in which he created a series of stencils, then smuggled them to various spots around Britain and used one or more of them to build up intricate and often sophisticated images, sometimes adding freehand strokes to the stenciled areas. His pieces often feature wry comments spray-painted next to or within the images. Subjects have ranged from small single-color rats (a frequent motif) to huge murals of policemen in riot gear dancing with daisies. He’s often created life-sized people or animals, including policemen kissing each other and children in surprising situations. His messages are usually usually anti-war, anti-capitalist or anti-establishment.

Over time, Banksy’s wit, talent and cleverness at hiding his identity made him a cult figure, and his art became so desired and in such great demand that people began removing his works from walls, cutting chunks out of tagged buildings and selling them at auction, even on eBay. He has created a number of pieces on canvas as well, and they now sell for grand sums at no less august an institution than Sotheby’s.

Banksy often paints works that mimic the style and subject matter of old masters but which show clever twists, such as a 17th century village scene in which the buildings are covered in modern graffiti. He has repeatedly smuggled his paintings into major art galleries such as the Tate in London and New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum, then hung each piece, complete with fancy frame and descriptive placard, among famous masterpieces. Sometimes museums have taken weeks to discover the subterfuge before removing his works. In 2005 his version of a primitive Lascaux-style cave painting depicting a human figure hunting wildlife while pushing a shopping cart was hung in the British Museum. When it was discovered, the British Museum, home to such important pieces as the Rosetta Stone and the Parthenon’s Elgin Marbles, wisely added Banksy’s painting to the permanent collection.

Despite his remarkably varied artistic talent, Banksy fits well into the graffiti artist or “street artist” genre because of his guerilla-style illegal forays into public places, which he then vandalizes, albeit wittily and with great skill, leaving evidence of his cunning alongside artistic talent. Many street artists have more swagger than technical skill, and the “Screw you, society!” anarchic message their graffiti announces to the world is usually more compelling than the actual art they produce. Banksy is not unusual among graffitists in his desire to remain anonymous and avoid arrest for his illegal activities, but he does show particular skill, subtlety and cleverness.

Some of his ruses, such as cutting a red British telephone box in half, reassembling it and welding it so looks as if it’s been hacked in two and bent, and then burying a hatchet in it, take not just daring and skill but some major resources to create, transport and maneuver into place. For fun several years ago, he counterfeited a million pounds worth of British currency with the face of Princess Diana taking the place of Queen Elizabeth II, but the results were so believable that attempts to spend the faux currency were all too successful, and he ended up with boxes of funny-money that he didn’t dare distribute for fear of being prosecuted for a federal crime.

Banksy’s story is perhaps the most compelling one in the world of graffiti art, but it takes an unexpected back seat to the story of his videographer in the Banksy-made film Exit Through the Gift Shop. The documentary made a splash at the Sundance Film Festival in January and is packing arthouse cinemas around the world just a few months after its debut. The gist of the story is this: In the 1990s, Thierry Guetta, a French-born entrepreneur, ran a successful LA clothing boutique which sold vintage rock-and-roller and punky clothes which he bought for almost nothing in scrap bundles and sold for obscenely high prices. On the side, he began obsessively videotaping everything, including the illegal activities of his cousin, a French graffiti artist who made small mosaics based on bit-mapped Space Invaders videogame characters. His cousin, who called himself Space Invader, allowed Guetta to film him gluing his guerilla-art mosaics around Europe and America, and Guetta’s videotaping obsession finally had a focus. He started documenting almost all the top players in the street art movement to the exclusion of doing almost anything else throughout the 1990s and most of the 2000s.

One artist who allowed Guetta constant access was Shepard Fairey, first famous for spreading over a million images of Andre the Giant‘s face on stickers and posters around the world, all atop the word OBEY, as if he were the ubiquitous Big Brother of Orwell’s distopian classic 1984. Later Fairey became famous for the red and blue poster of Barack Obama above the word HOPE that becames an official image of Obama’s campaign and has since been endlessly parodied. Fairey is now being sued by the Associated Press because he didn’t have permission to use the AP photo he based the poster on. A likeable guy who gets around, Fairey had become friendly with Banksy. Fairey was impressed after seeing Guetta’s obsessive compulsion to document graffitists and Guetta’s willingness to put himself in harm’s way and spend his own money and time helping Fairey and other street artists create and hang their work. According to the documentary, he felt Guetta could be trusted to meet and even videotape Banksy when Banksy came to Los Angeles. Guetta proved himself an extremely willing, friendly and helpful assistant, driving Banksy around, showing him the best public walls on which to ply his craft, and making his life and his art easier. Banksy soon allowed Guetta to film him at work, trusting that Guetta would keep his identity safe, which he did.

Here’s where the questions of who is an artist and what is art get confused. If you want to keep the upshot of the documentary a mystery, you might want to skip the next three paragraphs.

Eventually, Banksy felt it was time for Thierry Guetta to edit his huge collection of Banksy videos into a documentary, something Guetta had said he would eventually do but for which he had no training or experience. According to Banksy, after six months Guetta had cobbled together a headache-inducing, chopped-and-diced fiasco of a film without any narrative at all, a barrage of undifferentiated random images from his thousands of uncataloged videotapes of Banksy and other graffiti artists. Upon seeing this mess, Banksy suggested that Thierry give over access to all the videos and Banksy himself would create a movie out of them. To distract Guetta, Banksy suggested that Guetta should go off for six months and create art of his own and then have a little show. This made some sort of sense; the videographer had started doing some stencils of himself around LA and signing them MBW, which he said stood for Mr. Brainwash. Banksy thought Guetta would have a small vanity show someplace and the distraction would get him out of Banksy’s hair while Banksy put together a reasonable documentary out of Guetta’s frightening mishmash of videotape.

However, Guetta, now consumed with the idea that he was an artiste who could make a fortune and have a giant, splashy, expensive solo show that would wow the world, mortaged his house, hired a cadre of actual artists, prop designers and contractors, and rented a huge, expensive space in downtown LA. He told other artists to make largely unattractive knock-offs of Andy Warhol-style pop art pieces and spray painted silkscreen images of pop culture icons, claimed and signed them all as his own work, and relentlessly hyped himself around LA as the next big thing. Seven thousand people lined up to see Mr. Brainwash’s opening and his hundreds of derivative paintings, many of them created by others with almost no or no input from Guetta at all.

LA loved him. He sold a million dollars worth of “art” in two weeks. So many people flooded the gallery that what had been expected to be a two-week show stayed up for two months. Madonna asked him to create a Warholesque image of her for her latest greatest hits album. Mr. Brainwash has his first New York show this spring. And the joke was on Banksy. Or was it? While it illustrates the phoniness of the art world that he’s always reviled and parodied, a significant contingent of art world critics and followers believe they recognize the clever guiding hand of Banksy himself behind this cynical, clever and amusing film; they believe he put up the money for Guetta’s show and is using Guetta as a frontman for his ruse.

Whether this is a clever con or simply a wild situation that spun out of control while Banksy was distracted by the editing down of Guetta’s archive of tapes, it is a perfect illustration of the sort of art world nonsense Banksy has always opposed. Banksy has staged it as the story of an authentic (if anarchistic) hermitic artist who hides out among us and goes by a pseudonym vs. the faux-artist con-man entrepreneur with little if any talent for art and no insight into what makes it good, important or inspiring. Even when Banksy has created art meant to be sold to the throngs angling to pay real money to own a genuine Banksy, he has happily bitten the hands that feed him.

In 2007, Sotheby’s auction house auctioned off three of his pieces for a total of over £170,000; to coincide with the second day of auctions, Banksy updated his website with a new image of an auction house scene showing people bidding on a picture that said, “I Can’t Believe You Morons Actually Buy This Shit.” In his quest to meet and videotape all the bright lights of the street art movement, Guetta, on the other hand, became so hungry to be seen as a creator and star rather than part of the supporting cast of the art world that he created a huge show out of nothing but borrowed money and chutzpah, and, horribly, pulled it off.

The question of whether what guerilla street artists do (trespassing and defacing property that is not theirs) is ethical or justifiable is never addressed in this film. That’s understandable; Banksy is an outlaw hero who probably sees himself as akin to Butch Cassidy or Robin Hood, someone who points out the flaws in the system in an outrageously public way while remaining essentially invisible, only popping out often enough to build his legend and prove his existence. There’s no reason why such a person would want to draw attention to the dark side of what he does, especially when he doesn’t appear to recognize any darkness in it.

A film this cleverly and entertainingly made adds to his allure and stature while presenting his actions in the best possible light. Without ever explaining or justifying himself, he wangles his way into the audience’s affections and makes the story unfold in a way that builds sympathy for the characters, all of whom are literal outlaws. We find ourselves rooting for them to get away with their trespasses without ever feeling like we’re being manipulated or spoonfed with obvious and unnecessary explanations or justifications. Banksy really knows how to tell and sell a story, and, like a sleight-of-hand master, how to distract us from many of the important issues without our stopping to think, hey, what about the elephant in the room?

Speaking of which, there’s a great scene in which Banksy places an actual live elephant in the middle of a gallery show in order to prove a point. Of course, the point is lost on the media; they report that PETA (and LA Animal Services) didn’t like him painting an elephant with children’s facepaints and putting it on display, which is indeed newsworthy, but they seemed to have no concern with what the point of his painting the elephant was. This example of his disdain for people who don’t think about the meaning or point of art is astute, but it also shows his arrogance in thinking that, because others don’t share his sophisticated ideas and opinions on art, their own tastes, questions and concerns about what he does and how he does it are not just debatable but abominable proof of their philistinism. While I share his disappointment that people are so happy to accept pop culture simplifications of art rather than develop opinions of their own, I find his open contempt for people who don’t share his worldview distressingly self-absorbed and arrogant.

Banksy shows himself to be a witty and articulate man, both via his art and in the speeches he makes to the camera in this documentary. He speaks and gesticulates while wearing a dark hoody that obscures his face and and has his voice altered digitally. He could have been interviewed off camera and had the documentary’s narrator Rhys Ifans, the dryly entertaining Welsh actor, repeat his words to ensure that nobody could recognize his speech patterns or accent, but Banksy clearly enjoys scooting out of the shadows just a bit, providing blurry-faced proof of his escapades to the world via Guetta’s videos, letting people hear his accent, albeit in altered form. He is playing with his anonymity here, heightening the drama yet again, just as he does in his art, working the darkness and spray cans and stencils until he’s constructed a shadowy version of himself that he can carefully control access to.

Banksy appears to have a strong system of values (often fine ones, like looking out for the little guy and avoiding governmental tyranny), but seems to have little respect for the rights of others whose values differ (such as those who own property which he would like to cover in examples of his self-expression). This places him squarely alongside other heroes of the anarchistic British punk movement who have determined that destruction and defacement of things that they don’t value is justification enough for ignoring laws which seek to respect property and and which respect the needs of a society based on the rule of law.

In an attempt to focus attention on exploitative flaws in the capitalist system, socialists or, even further to the left on the political spectrum, anarchists like Banksy sometimes feel justified in ignoring property rights entirely, saying they are an artificial and damaging construct which enslaves the poor and empowers the rich, thus denying basic human rights and dignity. If you believe that an entire system is wrong, it can be tempting to determine that you will no longer acknowledge its rules or its power over you and decide to do things your own way. But just as unfettered capitalism can lead to great selfishness and a lack of awareness or concern for the needs of others, unfettered socialism can lead to societies which refuse to give incentives or rewards for exceptional efforts or remarkable talents, and which can be perverted into unhealthy organisms which stamp out originality or innovation. Fortunately, hybrid societies with capitalistic bases and strong (though imperfect) social safety nets exist in several nations around the world. They show that a respect for the innate worth of every individual and the responsibility of society to look after its weakest members can be balanced with respect and recompense for exceptional talent and effort. They also show that respecting a person’s property rights is an important component in respecting the person herself. No nation balances these opposing needs perfectly, but it is encouraging that millions around the world still strive to perfect their systems.

A healthy and safe hybrid society runs on respect for all the people in it, as well as for their legally-obtained possessions. And while Banksy has often shown himself to have a certain integrity, pointing out flaws in the art world and questioning the values of modern society, he has also shown a willingness to profit (sometimes enormously) by engaging in the same art world he mocks. To have true integrity, one could argue that he would have to turn down chances to make money off his art, but by selling works directly through Sotheby’s, even as he mocks the process, he has become a part of the system he claims to disdain. On the one hand, I want to see someone so talented and original, someone of his wit and insight and great skill, benefit from his ability and be able to make a good living as an artist. On the other hand, it saddens me to see him revel in becoming rich off the sale of his own private possessions while feeling no compunction about messing with the possessions of others and mocking the owners in the process. He then makes those whose property he has vandalized look bad when they seek to remove his art, even though, if they leave it in place, they give a message to all graffiti artists and other vandals that if you’re famous and clever or do a good enough job at it, the rules of respecting other’s space and property no longer apply.

A society which makes exceptions for disrespect of property and laws of trespass invites evisceration of the social compact. Sad as I am to see some of Banksy’s work disappear, I cannot blame the owners of the defaced spaces for showing their resolve not to let themselves become victims of vandalism, even clever or attractive vandalism, without a fight. Furthermore, Banksy knows that much of his work will be defaced or destroyed; he has chosen his medium and locations for precisely this reason. The impermanence makes seeing it as quickly as possible imperative, and that makes him an extra hot commodity and burnishes his oppressed outlaw image. It makes him a romantic figure of brash mystery.

Banksy can act as cynical about the superficialities of the art world as he wants, but he’s making huge sums of money off that very world nowadays, so he’s benefiting from the system he finds so corrupt. His hands aren’t clean, either.